It’s just genes, two different specialists explained. Genes that pulled at my heel and twisted my foot and flattened my arch over six decades. “Your calves are a beast,” the surgeon said, not referring to size or strength (sadly), but to pulling power. Fixing the foot, they promised, would allow me to walk and hike and travel for the rest of my life, whereas I had arrived at the point of no longer being able to walk for exercise. Sitting in the consult chair, I remembered Dad grimacing and clinging to his walker handles, sliding his deformed feet along, his ankle bones on the floor. “Let’s do it,” I said, and scheduled the surgery. Jeanette flew up for five days to take care of me, and, especially important, to take care of Mom. I would be either in my bed or in my office recliner, my foot above my heart, for a month, and no weight-bearing for two. “I want to see Roger,” clamored Mom the day I came home from the hospital. “I want to give him a massage.” Jeanette had gently suggested to Mom that “Roger will not want a massage.” A massage? Mom can still surprise me, apparently. Just where did the massage idea come from? And where did she imagine she would massage me? Not my sutured foot, certainly. My good foot? My bare knees? My bald head? The thought was too weird to study seriously. During her first short visit to my room, she stood over my feet with her fingers wiggling eagerly in the air, and I nearly screamed, “Don’t touch my foot!” She wasn’t going to massage me, of course, or even touch me. She was just sending me a little old-mother love through her wiggling fingertips.

Tag Archives: Caregiving

The Dementia Dossier: I Can Take Care of Myself!

I explained to Mom the pressure I live with every day of every week of the year of her wanting to go for a drive every day of every week of the year, and how tired I am of feeling that pressure. “Every time I leave the house, you look sad and disappointed,” I said. “And every time I don’t take you with me to run an errand, you look sad and disappointed. And you get upset with me every time you have a letter to mail and I don’t drive you right away to Help-U-Mail or the post office.” I explained how her 89-year-old friend LaWynn has someone come every day just to talk, or to play games, or to take her for a drive or to run an errand, or to make her lunch, or to change a lightbulb, or…. “I don’t need some stranger to come and play games with me,” she huffed. “I’m very happy with my blanket and my needlepoint and my word search puzzles—I don’t need someone to come and play games with me. I can take care of myself!” No. She can’t. Today I called five companion care companies to compare their abilities and rates. I have consulted my siblings and have their support. The reality is that within 30 seconds of meeting her care companion, Mom will adore her and anxiously await her next visit. She will love playing Rummikub and Boggle and Scrabble. She will love being driven around the neighborhoods. She will love her tuna sandwiches. She will love her letters being safely and immediately mailed. She will love not waiting a week or a month for a lightbulb to be changed. She will love love love telling a stranger all about growing up in rural Magna before it became an endless ocean of subdivisions and strip malls, and about her English and French and Swedish and Italian and Danish ancestors. She will love the hugs. We’re doing this.

(Image by Vilius Kukanauskas from Pixabay.)

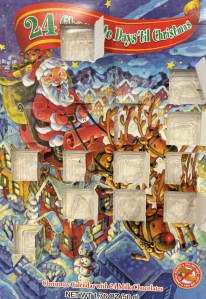

The Dementia Dossier: December Advent

At the grocery store, I spied at the head of the checkout aisle a children’s chocolate advent calendar. The price? $2.59. Each December day leading to Christmas, a child can open a perforated paper window to retrieve a small chocolate prize. I thought Mom might enjoy the calendar, and the chocolate—she is more and more childlike, after all. She was thrilled when I gave her the calendar and explain its purpose. With both discipline and curious anticipation, she opened one window every day, delighted to see the sweet prize that lay inside. Every day she shouted to me with glee, “Guess what I got today?!” from the advent calendar. One day it was a candle. Another day an angel, or a lamb, or a star. This cheap little children’s advent calendar gave Mom more meaning and enjoyment in the celebration of Christ’s birth than any other single activity or decoration. Who would have thought? I will definitely be keeping this new holiday tradition in the years to come. Something so small was to Mom something so important.

The Dementia Dossier: Mentos Blue

I finally said something. We were watching on television a Christmas special from the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square. At high volume. And still, above the orchestra brass and 360-voice choir, I could hear the smacking of Mom’s gum as she chewed and sucked on it with obvious enjoyment. But I couldn’t stand the sounds any longer, wincing at every smack syncopating the music. “Mom, I can hear your gum-smacking above the orchestra!” She looked hurt. “I don’t want to hurt your feeling, Mom,” which was true, “but it’s loud,” which was also true. I quickly changed the subject, commenting on the expert singing of the soloist. One convenient characteristic of Mom’s deepening dementia is that she quickly forgets her hurts and disappointments, returning to cheerfulness. In fact, she quickly forgets most everything, except things like the names of the cemeteries where her grandparents and great-grandparents are buried, or the road names of the New Jersey town where we grew up, and from where Dad and Mom retired nearly 30 years ago, leaving forever for Utah. Mom and I returned to our television show, and while she returned to her normal good cheer, I did notice that the gum smacking had diminished…for now.

The Dementia Dossier: Ice Cubes

The water line to the refrigerator’s ice maker cracked years ago, ruined the kitchen’s oak-wood floor, and was permanently abandoned. My daughter Laura has an amazing countertop ice-maker, producing pleasing, soft-crunchy cubes of pellet ice. But Mom opted for a dozen of the old ice cube trays. I confess to using my share of ice cubes for the day’s cold drinks, but it seems that every day I reach into the freezer only to find an empty ice bin. Mom’s household routine used to include filling the empty trays at the kitchen sink and carrying them expertly to the freezer, without spilling: two stacks, six-high. But with her walker a necessary tool of her daily perambulating, the chore has more often fallen to me. With a busy schedule, running from one task and job and activity to another all the day long, the mental stoppage of finding the empty ice bin and needing to empty the ice cube trays into the bin and then to fill the trays with new water, has been a real irritant. Mom uses by far more ice that I do, so I naturally expect her to fill the trays. (Can I hear my readers offering sympathetic words of “Aw, you poor thing?” I thank you.) One reason the ice runs out so quickly is that Mom fills the trays only halfway, yielding half-cubes, naturally. I, on the other hand, fill the trays completely, to yield large cubes lasting us twice as long. Mom beat me to the job of filling the trays the other day: when, all twelve trays of cubes barely filled the bin. “Mom,” I whined. “Why do you fill the trays only half-full?” Looking downcast, she explained, “I don’t like such big cubes.” Besides her daytime use, her nighttime habit is to take a cup-full of cubes to her bedroom, to suck on them during her bedtime routine—and now I understand the desire for half-cubes. The big cubes really are impossibly uncomfortably big and sharp to fit into one’s mouth and enjoy. In fact, it might be similar to cramming a whole apple into one’s mouth instead of enjoying one reasonable bite at a time. Half cubes it is, then.

The Dementia Dossier: The End of the World

Mom’s computer printouts have been coming out more and more purplish-red as the black ink ran out and the color cartridge eked out its last. “Looks like you’ll need new ink very soon,” I observed. This morning, she rolled herself and her walker into the kitchen and gave me a look of panic and consternation. “You’re giving me a look that says the world is ending,” I observed. It was…for her. I had noticed earlier on her desk a page printed red on the top half of the page only, and faded into nothing for the bottom half. “My printer won’t work!” she shouted, more in anxiety than anger. I reminded her she was running out of ink. “I know…I tried to put the new cartridge in…but I couldn’t do it.” Indeed, she had inserted the new cartridge, but incorrectly, and it was stuck fast in its slot. HP had designed its cartridge bays so that when an 86-year-old tries to install her own cartridge, she will do it wrong and not be able to remove it and will panic and give up and will need a new printer. I worked and worked to remove that cartridge, but it had clicked in incorrectly and was locked in. I looked like a quack surgeon, with my headlamp and instruments operating on the printer’s innards. With no little force and a great deal of twisting and prying, the cartridge finally released. But not before staining my thumbs. Baby wipes wouldn’t clean them. An alcohol-soaked cotton ball wouldn’t clean them. Soap and water? Nope. I’ll try mineral spirits next, I guess. I have to give Mom credit, though, for trying to solve her own problem before coming to me.

The Dementia Dossier: Arthritis In My Knees

Mom’s knees pain her and are weak and wobbly with arthritis. “I feel like I might fall,” she often says. You can’t fall, I want to say. If you fall, your life in this house will be over. At the nearby hospital, the orthopedic doctor prepared to inject cortisone into her knees. I asked him questions about injection dosage and frequency, and he answered that the dosage was fixed, standard, and the injections could be administered only every three months. I thanked him for the information. The doctor asked Mom if she had any questions. “Do you want me to pull my pants down now?” was her answer. I felt a bit embarrassed as the doctor shifted on his feet and stammered a suggestion that maybe she could lift her pant legs. She could not. Down came her pants. In went the needles. “I hope the shots help, Mom,” I managed as I wheeled her out to the car. They did not.

The Dementia Dossier: Rigid Dementia Routines

A month after my involuntary retirement, and the illness that followed, I finally found the mental energy to map out a new routine for my daily life. My routine involved time for reading scripture, exercising, new writing projects, painting lessons, low-bono work with an immigration non-profit, and yard and house projects. I also built in time to take Mom for her necessary errands, like the post office or the pharmacy. Since Mom is so routine-bound in her dementia, Jeanette suggested Mom would benefit greatly from seeing my schedule, knowing my routine, and knowing that she was a part of it. I printed the schedule, and Mom taped it to the lamp next to her recliner, where she could always see it. I knew a routine would need to be flexible. Without flexibility, the routine would cease to be the servant and become the master. Instead of the routine serving my purpose, I could become a slave to the routine. That flexibility proved necessary as I succumbed to sinus and bronchial infections that laid me flat for much of eight weeks and dragged me through two ten-day microbiome-depleting rounds of antibiotics. The illness destroyed my routine. But every day near 2:00 p.m., Mom asked—according to my routine—to be taken to Help U Mail or Walgreen’s or out for a drive: Ahhh! Just look at the beautiful blue sky! I began to roil with increasing resentment, and biting my tongue and clenching my teeth, I evenly uttered, “Mom, I don’t think you have a sense of reality right now about what I can do. I had just enough strength to watch Jeopardy with you for half-an-hour. I’m not up to an outing.” After more than two months, I am nearly recovered, but my routine remains in a shambles. Returning from an appointment at 4:00 p.m., I asked Mom how her afternoon had gone. “Quiet,” she answered, and continued under her breath: “I guess I’m stuck in the house today.” “Stuck?” I answered. She thinks she’s stuck in her recliner, I thought. She thinks I’m responsible for her getting unstuck. “You’re not stuck,” I challenged. “You can get up from your recliner and sit in a chair on the front porch and look at the blue sky, the clouds, the endless airplanes, the cars driving by. You can sit on the back porch and look the mountains with their maples turning red and the dustings of snow on the peaks. You can use your walker on the sidewalk for a quick walk.” And then I saw it. When I began my new retirement routine, I had made time for her in my daily schedule. My My schedule. She had taped my schedule to her lamp. And with that bit of adhesive tape, I became part of her routine and her schedule. I had been sucked in even further by her consuming dementia. I was now another symptom of her slavery to dementia routines. The next morning, I pulled the paper from her lamp and crumpled it into the trash.

The Dementia Dossier: Silk Pie

French silk chocolate Nutella cream pie in a toasted graham cracker crust. Ahhhh. “This is very possibly the most amazingly delicious thing I have ever tasted,” praised my son Brian at my birthday celebration. Not wanting to ask anyone to bake or buy a birthday cake for me, I had made my own, this luscious French silk chocolate Nutella cream pie in a toasted graham cracker crust. Everyone loved it. I could eat only a small taste because of how the sweet aggravated my searing sore throat. After the party, a plate with half the pie went into the fridge for Mom and me to enjoy later. I’ll have a slice for my lunch tomorrow, Mom said. I invited her to help herself to as much as she liked, only save me one piece, because I had labored two hours to make the pie and wanted to enjoy just one more slice when my throat felt better, despite dieting to reduce my sugars. And later in the week I was ready, my throat feeling great, my sugar intake dramatically decreased, ready for my last piece of silky smooth sweet. On opening the fridge, I found the plate gone. Mom, where is my pie? I told you to enjoy as much as you wanted but to save me just one piece. Do you remember I told you that? Just one piece? Confusion clouded her face as she mumbled, I guess I forgot. I’m sorry.

The Dementia Dossier: Resting

She’s up at 8. Like clockwork. Up at 8 and in the shower and down the stairs by 9 for her crunchy dry Cheerios and glass of milk on the side and a glass of hot tea in the incessantly beeping microwave begging for someone to come attend. And Monday is laundry day. And laundry comes after breakfast, beginning at 10 or so. I texted my mother about my illness and miserable night, about my aches and chills and inability to sleep, and about needing to rest, and she responded Me Too. But the water started flowing and squirting, and the washing mashing swooshing and spinning, with my head resting on its pillow and the pipes and drains and machine six inches away through the wall. Rest now futile, I stood in my bathrobe fuming and wondering and watching my mother jam the dowel into the soaked whites. You saw my text that I was sick and needed to rest, right? You know that my bed is just on the other side of the pipes and I can hear everything, like my head is inside the washer, right? Well, I waited for a while…but I was out of clean underwear. I’m just trying to understand what you were thinking. Because you could have done the laundry later, like at 1, or at 2, right, so I could rest? Well, I don’t know, I was out of clean underwear. This conversation came slowly, in snippets, as I gauged her capacity to absorb feedback without hurting her feelings, and like most such conversation with her, she had no capacity and did have hurt feelings, so I had failed again at discerning how to communicate through dementia. She seemed confused at the notion of delay and incapable of weighing priorities and convinced that her need for tomorrow’s clean underwear was paramount today, and she must do the laundry, now now now, before it was too late and the day had turned into late Monday or, forbit it, tomorrow.

The Dementia Dossier: Introduction

Many of you followed Courage at Twilight as I recounted my experience living with dying parents. With this page, I am launching a new exploration. As my father’s mental abilities diminished, I naturally attributed the loss to senility, or more broadly and accurately, to dementia. He read for hours and hours a day until the final week, and he still comprehended and remembered more than I do when I read the same books. But his ability to comprehend, synthesize, apply, and remember the information began to suffer. The decline was mostly masked by his great intellect, but gradually became more noticeable. Where nine years ago he easily followed Word’s “accept” and “reject” functions while reviewing my suggested edits to his book Process of Atonement, in his last year he could not manage the power button, mute button, or any other button on the television remote. Alone with Mom now, I am observing on a daily basis her decline in mental function, short-term and long-term memory, and the ability to process new information and work through new problems. And I am pondering the spectrum of mental normalcy. I am well-known at work for remembering the details of 30-year-old incidents, but I notice my own mid-term memory fading, like forgetting that the City Council increased its golf course fees six months ago (I wrote the fee resolution). I am wondering: where does sanity end and senility begin? But that is the wrong question, presupposing that senility is the loss of sanity. It isn’t. Senility is the loss of memory. And don’t we all experience memory loss for once-remembered people, places, dates, and occasions? So, by becoming more forgetful, am I, myself, drifting into dementia? Where does dementia begin? On what date is my memory and cognitive function loss sufficient to say, “That’s when my dementia began”? I doubt such a date can be determined. But episodes characterizing dementia can be humorous, sad, or maddening (etc.), or all combined. In these posts I will record my mother’s little oddities, pointing together toward dementia and decline. I mean no disrespect in finding an aspect of humor in her decline. But humor often derives from the little human oddities of life, whether happy or sad. I am merely observing, and trying to make sense, again, of the ending of life. Each post here will be much shorter than this one—I promise—and will relate a small vignette illustrating the nature of inevitable human decline. I love and respect my mother—and she also drives me batty! Hopefully these entries will make you smile at, and ponder on, those we love whose earthly lives are winding down. I look forward to continuing my journey through life with you.

Courage at Twilight: The After Words (Privilege)

For every day of this caregiving experience, I have been conscious of the blessings, the resources, the benefits, the privileges that shaped and enabled the experience. By “privileged” I simply mean to indicate our relative place on that vast spectrum of personal resources, our being somewhere in the in-between of those with tragically few resources and those with unnecessarily huge resources. My caregiving experience, and my father’s and mother’s experience as the cared-for, undeniable was shaped and even determined by our relative resources. My father’s pension allowed us to hire private-pay home health care and hospice, which sent aides for two hours a day, seven days a week, including holidays, for the last two years (about $30,000 per year). To be sure, the costs ate away steadily at my parents’ savings, but the fact remains that they had savings, whereas many do not. Not having this resource would have made my caregiving experience impossible, at least for me. Add to our privileges the ability to purchase a $14,000 chair lift for the staircase. While the lift was a major hit to our budget, we had the budget. Add the blessings of medical insurance, prescription insurance, and social security. Include the allowance I was given to work a flexible work schedule, which enabled me to cook healthy from-scratch meals from fresh ingredients. While I am only a small-town government lawyer, my professional knowledge and social clout did clear obstacles others struggle to break through. Our relative privileges do nothing to reduce the legitimacy or reality of my experience and my story. But they do shape that story. A lack of these resources would have dramatically altered the experience, and dramatically multiplied the stress and trauma, and I acknowledge the difficulties faced by persons with fewer resources. I am not a community organizer, and offer no social solutions, but I am aware of some of the challenges and struggles faced by many. It may be a cop out to say I would not have been up to the task without our resources, but I fear I would not have been up to the task.

(Pictured: funeral planter from the Tooele City Mayor and City Council.)

Courage at Twilight: The After Words (Loneliness)

We, my brother and sisters and I, navigated a week of days too filled with tasks to feel much grief—writing an obituary that attempted to summarize in two pages the long life of a great man—preparing a funeral program involving dozens of family members—writing a funeral talk I did not want to write—the mortuary checklists—settling affairs of estate—hundreds of texts and emails and messages to and from those who knew and loved him—the trickles and gushes of people through the house—all the standard tasks, which we were determined to perform in an exceptional manner. Mom will be lonelier now, without her husband and friend of 65 years. She will not hear him say as she sidles past his hospital bed, “You’re just the most wonderful wife, Lucille. I love you. We’ve been married 62 years. When you walk by, I’ll give you a hug.” I will not hear him exclaim “Roger! Welcome home!” and “What a gorgeous dinner, Rog! I just love steamed vechtables!” Walking the grocery store aisles, I passed the zero sugar mint patties, the deluxe mixed nuts, the lidocaine foot lotion, the Brussels sprouts (Mom hates them), and no longer put them in the cart. And, I felt the wrench of good-byes anew when I handed to the thrift store attendant the bags stuffed full of shoes and socks and shirts and sweats and suit coats and hoodies. But our grinding struggle is over, and Mom will experience her widow’s aloneness with a new measure of calm. A neighbor asked Mom how she was feeling, and she declared, “I’m so happy for my husband. He’s not paralyzed or sick anymore. He can run and jump and play. He’s with Sarah, and with his mother, his father, his sister Louise, and all the rest.”

Courage at Twilight: I Haven’t Lost My Mind

Dad asked me to make an entry in his check registry, in which he keeps a scrawled and unnumbered untallied record of his checks. And that is where I discovered the $500 check made out to his dear hospice nurse. The image of the entry bounced erratically around my brain for hours, seeking but finding no possibility of legitimacy. I asked Mom and Dad if I could discuss something with them (“Certainly!”), explained about finding the registry entry, and asked what they could tell me anything about it. Dad offhanded the check as a simple Christmas gift, and turned back to his book. I pressed him about why this gift in this amount to this person. “I just thought she needed it,” he demurred, not looking up. I pressed further: but what did she say that led you to believe she needed money? He mumbled something about hard times and her husband being out of work, with Christmas coming. I launched, carefully, into a lecture about his days of monetary magnanimity being over, that his bank balance was low and diminishing, that giving his money away sabotaged my ability to take care of him, that my fiduciary duty to him required me to raise the subject of financial irregularities with him, and that, besides all these, his hospice nurse playing on his sympathies and accepting a gift violated hospice company policies, Medicare hospice licensure rules, and nursing ethics. What’s more, for a person in a position of trust and confidence (like a hospice nurse) with a vulnerable adult (like him) to obtain that vulnerable adult’s funds (like a $500 check), constitutes the crime of exploitation of a vulnerable adult. But I asked her if there were any rules that prevented her from accepting a gift, and she said no. Just a week earlier, Jeanette had warned Dad about another exploitative person who might ask him for money, and he had retorted that he could “recognize a con.” And yet here he had been conned. “I haven’t lost my mind,” he insisted to me, but he could see now he had been played, and he felt embarrassed. “I won’t do that again,” he promised. He looked to Mom, “We won’t do that again.” Lying in bed pondering the bizarre situation, I realized I possessed a new power, namely, the power to get the nurse fired: a power I did not want. We liked this nurse; we trusted her; she is a nice woman and a good nurse; and I did not relish reporting her and causing her pain. And that is part of the con. My sympathies were being played, too. So, I used the power I had been given: I called my contact at the hospice company and reported the occurrence of the gift. The same afternoon the company director called to tell me the gift had been investigated and confirmed, the nurse had been fired, the nurse would be referred to the Board of Nursing, and the $500 would be reimbursed. Thank you so much for calling. Sudden and severe, but not surprising. I fought to not feel responsible for the devastation just wrought in the life of the nurse and her family, due to my report, urging my brain to believe the truth that these were direct and terrible consequences of her actions, not mine. But I will not tell Dad that I reported the nurse and that she was fired, because his brain would lose the battle, and he would berate himself for giving the forbidden gift and destroying the gifted.

(Pictured: brick wall, with ivy, surrounding my daughter’s Chicago apartment back patio.)

Courage at Twilight: Nobody Cares

Ten p.m. The hated hour. The impossible hour. The hour of transfer from recliner to walker seat. The hour of rolling dragging backward to the bedroom. The hour of transfer to the edge of the bed, to enough of the edge to stay on and scoot farther in, and hopefully enough not to slide off and fall to the floor. The impossible hated hour. He doesn’t want me here, Dad doesn’t. He knows he’s poised on a precipice: “I don’t know if I can do it.” He knows some unseen stress is getting to me, that I am on edge and irritable, and has no idea it has to do with him. “Where’s Lucille?” he demanded, looking to her to lift his butt, though she can’t, pretending he doesn’t need me, though he does. “I won’t do it without Lucille.” On this night, gripping the armrests to make the impossible effort, he looked up at me in his nakedness and remarked how sixty years ago he was a student in Brazil, and I was a baby, and I dutifully observed in return what a long time ago that was. But he persisted and began rehearsing to me one of his many mystical stories, this one about being assigned to visit ten families who no longer came to church, ten families who had no phones or cars (neither did he), ten families who lived far from the church building and from each other and from him, families whom he visited every month for the school year he was there, riding buses in the vast internecines of São Paulo, urging them to Christ, inviting them to church, making the last visit as my first birthday neared, and hearing the voice of his Savior assuring him that his offering of service to the ten families had been seen and accepted. But as he began the old story, looking into my face with the earnestness of someone having something of utter importance to say that had never been said or heard in the long history of the world, I walked away, having absolutely desiccated internal emotional reserves, muttering that I had something in the oven that needed tending, and indeed I did have something in the oven, for the second time, because I had baked the miniature mincemeat pies for the first time on the wrong temperature and now I hoped to salvage them for an office party the next day. “Never mind,” he said, and he looked up at Mom imploringly: “This is important. And nobody cares.” Back from the oven, my own heat rising, I rebutted with how unfair that was to me, and how of course I cared, and how I have heard the story a dozen times and did not need to hear it again, and how I had something in the oven that needed tending, and how I had a lot going on in that moment, and how I was tired and wanted to go to bed. Another painful barefoot moment on the razor’s edge of being needed but not wanted passed, and I hung back in offering a steadying arm under his armpit until the moment just preceding a would-be fall. Somehow he made it to the edge of the bed. “Good-night, Mom and Dad.” From where I sat in the living room, piecing together the faces of angels and shepherds and sheep, I listening to his gravelly petition to his Heavenly Father, praying for me, praying that I will not be angry, that I will be blessed in my hardships, that He will be with me, totally unaware of the cause of my feelings. Placing the Jesus piece in the Nativity puzzle, I breathed, “Blessed Jesus, let me not do this to my children.” Let me leave this planet before this, knowing they will weep for a day and then get on with their joyful challenging bitter hopeful grinding lives, with me a happy memory instead of an angry silence or an endlessly repeating story of a glorious romantic mystical reinvented past.

(Pictured: my own brickwork in an antique-themed writing studio within my old chicken coop.)

Courage at Twilight: I’m Worried

Mom served Dad his can-of-soup lunch at 2:53 p.m., and he said hopefully that he hoped they didn’t have to watch the last seven minutes of Family Feud. “I don’t care what you want!” she snarled, hoping precisely to watch the last seven minutes of Family Feud. At the kitchen sink, I turned to look at her in disbelief, raising my shoulders and hands in a What was that? gesture of irritated incomprehension. None of us said a word, but she had seen me, and turned on Dr. Pol. I guess she is done being bossed by the boss, the man of the house. And now she possesses the marvelous power of the TV remote. That morning, I had driven to a temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a beautiful edifice, a place apart from the cares and worries of the world, where we dress in the symbolic equality and purity of all-white, and learn about God’s plan for humanity and about our place in the vast universe, our origin and destiny, and we make promises to be good and chaste and generous and faithful to the faith and to the Church and to our God and to each other. In the temples, we act as proxies for the departed, being baptized on their behalf, and linking them together for eternity (if they wish it) in their mortal family units as couples and as parents and children. I had come for peace, for inspiration, for answers, for a settling of the spirit. But sitting in the bright room with chiseled carpets and gold leaf wall accents and gorgeously upholstered chairs and elegant inlaid wood tables and brilliantly colored stained glass and tinkling sparkling crystal chandeliers, sitting and seeking some peace, all I could hear in my head was Dad repeating his ruminations: “I’m worried about…” (insert the name of any one of his two dozen grandchildren, of any one of his dozen CNAs, of any one of his six children, etc.) hour after hour after day after week after month, endless cogitations about endless worries, repeated to me daily, and I let his rueful expression worm into my head and crowd my heart, and I let all the worries follow me into that quiet holy place, unworthy stowaways into the temple, to churn and swirl and tense my neck and back and distract me from the hopeful joyous prayers and promises, and fill me instead with dread and angst. And when I came home and he began again with “I’m worried about…” I changed the subject, I interrupted, I dodged and demurred, I pretended I had not heard him, and I launched into another subject, a small subject, a brief subject, then made the excuse of having work to do upstairs.

(Pictured: mountain stream in Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah.)

Courage at Twilight: Television Tyrant

“Is this asparagus?” Dad called out after I served him his dinner plate. “It tastes like a stick.” The only words my mind would form were profane, and I clenched my jaw against their audible escape. Perhaps he was trying to be funny? Or, perhaps his dementia really is that bad? The asparagus was very skinny, after all. But mighty tastily cooked. After the dinner-time Next Generation rerun, I retrieved the empty dinner plates—all the sticks on his plate were gone—and Mom began surfing the channels. Oh, the power. “We could watch ‘Superman’,” he suggested, catching a glimpse of the name on the screen. “No.” Mom answered simply. “We could watch ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’,” he ventured again. “NO!” she hollered. She was in total control. He was helpless, defeated, and he knew it. I fled the kitchen, weary of the too-frequent tyrannical television exchange. At 10:00 p.m., when I wanted to be in bed, I descended the stairs to the family room, the scene of a terrible nightly struggle. Dad’s task was simply to stand, to hang onto the walker handles while he turned, and to sit his bare bottom on the towel-covered walker seat. No steps required. A good thing, since he has no steps in him to take. He pushes, and he rocks, and he pushes, and he trembles, and he slowly rises from his recliner, his body bobbing convulsively from arms and legs that will no longer bear his bulk. His swollen feet shift an inch or two at a time in the 120-degree pivot. And there it was—I could see it: he was going down, and once he went down there would be nothing I could do but dial 9-1-1 and be up half the night with adrenaline and worry. So, I pressed a fist into his hip and shoved, and he groaned and slumped precisely into position and exploded angrily, “DON’T PUSH ME!” I had no patience for the petty power posturing, as if he could have positioned himself. I recognized that he was reacting to my maneuvering with the only power he had left: the attack. But I was having none of it. “DON’T YELL AT ME!” I retorted. “If it weren’t for me, you’d be on the floor!” I pulled the walker, Dad’s back toward the direction of travel, to his bedroom, his feet dragging uselessly behind, swollen and deformed. I will not give him the meager dignity of pushing the walker with him face-forward, not because I am spiteful, but because of his difficulty in inching his feet forward and my difficulty in not running over his hideous toes. So, I drag him. And I position him facing the bed for the last agonizing transfer of the day. “I don’t want any help, because I can do it myself, even though I’m slow.” Be my guest. I must be there anyway, just in case, and to spare Mom the labor and worry. And, somehow, every night, he pivots just enough to land his butt on the edge of the bed, barely. But I want to scream at him that he shouldn’t be here, at home, scaring everyone and bossing everyone and narrating the news in real time, a delayed echo competing with David Muir at volume 45, and complaining about eating sticks for dinner, and making Mom lift his butt. But, of course, he should be here: that is the whole purpose in my being here, so that he can be here, until his end. Though not wanting him to die, that purpose has exhausted me and left me angry and resentful despite my every effort to be the good, dutiful, patient, faithful son. At the Thanksgiving dinner table two days before, we sang one of our favorite family songs, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and Dad explained how it was an old slave song, the enslaved Black Americans supplicating God to send his fiery chariot to end their suffering and convey them to a merciful heaven. We have sung that song since I was a little boy, at home, around the campfire, at reunions. “One day, soon, that chariot will swing low for me,” he sighed.

(Pictured: fall leaves on an arched wooden bridge over a dry creek in Dimple Dell, Sandy, Utah.)

Courage at Twilight: Night Lights and Shadows

“Help him pull up his pants,” Mom instructed. I responded that I would help Dad if Dad needed help, but I wasn’t going to stand there waiting for him to need me, standing and waiting for something bad to happen. “I can’t just stand there waiting to see if he needs me, hovering, waiting, waiting, worrying for the next hard thing to happen. I can’t do it anymore. I can’t.” Twenty minutes later, Dad finally needed help pulling up his pants, and I was there to help. But I hadn’t hovered and waited and worried and worn myself out over it. I have to say, I don’t care, which, of course, means I care a great deal, but am weary of the worry of caring. After three accidents the next day, Dad admitted to me that he might have to start wearing a brief. The only way he will wear a brief is if the brief idea is his idea. I don’t bother suggesting. “Whatever you think you need, Dad.” So tired, I’m often in bed by 10 p.m., and often wake up at 11 or 12 feeling hungry, or I awaken for no apparent reason. To get past the master bedroom, I must traverse the light field cast by the outlet night light, sending daddy-long-legs shadows into their room, and as Dad lies in bed rehearsing to Mom the family’s challenges and blessing, he never fails to detect my quick passage, calling out without fail, “There goes Roger down the stairs to get a snack,” and I roll my eyes in the dark. Some nights I stand at light’s edge, wondering if the snack is worth being discovered and commented on, again. This morning, Dad rose from bed and strained to stand at his walker, at 8:30, and he immediately collapsed to the floor, too weak to move. Mom was in the shower. When she discovered him lying on the floor, she put a blanket over him and waited for an hour for the CNA to arrive. She phoned no one, not even me—she said Dad would not let her call. Instead, she sat in her chair watching her husband immobile and paralyzed on the bedroom floor. At 11 a neighbor texted me, “Hi, my wife mentioned that she saw some activity at your house this morning.” Some activity? What the hell did “some activity” mean? “Some activity” meant an ambulance and a fire truck pulled up to the house with flashing lights. The paramedics and firefighters—it took five of them—managed to hoist Dad off the floor. Dad will sleep is his recliner tonight. He is too weak to get himself to the chair lift. I have set him up with large absorptive pads underneath him and on the floor, with a urinal, with a portable toilet that he likely is too weak to reach, with blankets, with his feet raised and his body laid back, and with the very real question in his mind of how he will get through the night. Well, I can’t piss for him, or stand up for him, or walk for him. I can just give him what he needs, or try to, and respond to whatever happens.

Courage at Twilight: Noises in the Night

Bowing to the carpet—to investigate the yellow streak. I have come to hate the stench of urine. I don’t judge or malign the fact of urine—I hold no personal grudge. Urine is universal. But I loathe the smell. And entering the house today, acrid yellow vapors rushed up my nose. I hurried to mitigate the offensive odor by filling the carpet shampooer with soap and hot water and getting to work. The shampooer stands ready in its convenient corner for tomorrow’s use, for I will need it tomorrow, and the next day, etc. Noises, too, are triggering panicky heart beats and sweats. The squeals of school children running to the bus stop seem the screams of my mother in distress. The “thunk” of Mom’s magnetic shower door becomes the thud of my father falling. This morning’s Tchaikovsky bass drum booming might be, I wondered weirdly, Mom’s grief reaction to finding Dad dead in his recliner. Getting Dad situated in his new hospital bed, I felt zero confidence he could navigate the urinal in the night. I keep my bedroom door open at night now, listening for sounds I hope not to hear, lying awake in the quiet.

Courage at Twilight: Giving a Tug

“I want to go by the bushes and trees,” Dad insisted at the end of a wheelchair walk around the block. “Put on your list, for whenever you get around to it , to trim the junipers back from the sidewalk.” I was reluctant to do so, I said, worried I would cut off all the green and leave only the bare ugly inside sticks. “Do it anyway,” he said imperiously, admitting no discussion. And I bit out a stiff, “Yes, Sir.” Mom invited her doctor (and neighbor) over to see her needlepoints that adorn every wall. He politely wandered the house, exclaiming, “Oh my gosh!” at each frame, and she beamed. Quinn quizzed Dad from a paralegal coursebook. As 9:30 p.m. came, and Quinn asked Dad if he wanted to discuss another legal scenario, I bristled at the late hour and Dad’s flagging energy, but Dad answered “Absolutely!” and they kept at it, Dad’s legal mind as sharp as ever. I fled the house for a Saturday hike, a long hike, the longer away the better, and before the midpoint my phone dew-dropped with Mom’s text: Will you be home soon? I need you to take me on an errand. I responded, No, I will not be home soon. No, I will not be home, ever, I wanted to type. As I nursed my bottle of Gatorade after the hard hike, Dad randomly asked if I knew a particular song, and began croaking out “Sunny Side of the Street.” One of my favorite Frank Sinatra covers. Mom soon added her higher-pitched screech, and the melody flattened into a gravelly two-tone monotone. After the song, Dad struggled and shook to stand tall enough to push his walker toward the bathroom, dribbling along the way, muttering desperately, “Oh, God. Help me, Abba!” and cursing his routine “Damn!” as he worked to coordinate the walker, the door, the handrails, his pivot to sit down, and pushing down his sweat pants. “Rog, give my pants a tug,” he called on his journey back to his recliner. “I couldn’t pull them up by myself.” Yes, Sir. Oh, God. Help me, Abba.

Courage at Twilight: Living Through Me

Some people need to talk—a lot. Some people prefer to listen. A match of these two is fortunate. I have already described how Dad talks and tells his stories and expounds upon religion and history and morality and family and the contents of the encyclopedia, and how I am more of a listener who at 60 is weary of listening. Gloria, however is another talker. She cares for Dad several mornings a month, and the conversations begins rapid fire the moment she calls “Good morning!” from the top stair. When Gloria talks, Dad listens. When Dad talks, Gloria listens. Yet, somehow, they both seem to talk continuously. Today I caught snippets about Gloria’s sick cat and how the dry cat food and wet cat food each affect the cat’s weight and health and energy and general demeanor, and how the cat is slowly getting better with good cat food and care. Dad took his turn about the cosmic character of the universe with its gravity and dark matter and fusion and electromagnetic energy and relativity physics vis a vis quantum physics. Both are vaguely sympathetic to what the other is saying, but mostly they each appreciate being able to talk and being listened to. Did you know that a mere 20 years ago, the consensus among cosmologists and xenobiologists was the impossibility of intelligent life anywhere in the universe but on our Goldilocks Zone earth, but that today, with the James Webb telescope’s discoveries, the consensus has shifted to the statistical impossibility that intelligent life does not thrive among the trillions of habitable planets orbiting in the trillions of solar systems orbiting in the trillions of galaxies or our vast universe. Her cat prefers the wet food. We will never know because even light takes one hundred thousand light years to travel to us. The vet’s treatments are helping. Time for your shower, Nelson. I returned from my ten-mile Jordan River paddle long after Gloria had gone for the day. The olive-brown water ran at a 15-year high and swept us pleasantly downriver. The toughest stretch of the paddle was the half-mile portage through head-high thistles with mean mean thorns and willowy willows and sage brush, so aromatic, daisy-chain carrying our kayaks single-file to where we could cross the private hydroelectric dam that also splits the river into two enormous irrigation canals, the river itself suddenly shrinking by two-thirds. Weary and blistered and scratched upon arrival home, Dad called out with his usual cheer: “Roger! Welcome home!” followed by “Sit down and tell us all about it. The people. The river. The wildlife.” And so I told them about the thistles and dams and slow high olive-brown water, and the people, and the birds: the Clark’s grebes, cormorants, pelicans, belted kingfishers, Bullock’s orioles, avocets, ibis, phalaropes, terns, stilts, Canada geese, mallard ducks. I did not tell them how I was so eager in the twilight to show my friend Stephen a beaver and saw one in the shadows and called to Stephen “There! Beaver!” only to have the beaver sprout wings and take flight. “I think that’s a duck,” he dead panned, “or maybe a duck-beaver.”

Courage at Twilight: Fiercely Red

Mom stood. Up from her recliner. During a commercial break. “Are you going to the bathroom?” Dad asked with a touch of accusing panic, for the urge had struck, and he gets so little notice, and every second counts on the 12-foot journey. “Yes,” she spat. “Don’t worry, Dad,” I assured him, “she’ll be out by the time you’re up.” Dad sat, stymied. Sunk in his recliner. During the commercial break. He still had not stood when Mom came wandering into the kitchen, her business done, to check on my cooking. The Jeopardy buzzers buzzed. “Are you finished, Lucille?” Dad barked after the commercial break. “Yes,” she called. “Why didn’t you tell me?” he lobbed, struggling and shaking to stand and stoop over the walker, his time perilously past. “I’M FINISHED!” she hissed. “Didn’t you hear the flush?” A streak of white flashed in my periphery and something bounced hard against the kitchen window, two feet from me. I knew, of course, what it was, sort of, a bird, but my heart pounded anyway. We hustled outside to find the bird sitting in the dirt, a gray falcon or hawk of some kind, sitting awkwardly, wings askew, head rocked back on its neck. Its red eyes glared fiercely at us, and it panted rapidly with parted beak. Well, that’s the end of this bird. Its neck is broke. Such a startling beautiful creature. I was powerless to make a difference for the hawk, and let it be, returning sadly to my cooking. The children and grandchildren remained, marveling and sad. Then Lila screamed, and Brian poked his head through the door to tell me the bird had stood up and pushed off in flight. Well, I’m sure glad to be wrong. Audubon informed me the bird was a Northern Goshawk. The kitchen window had vinyl grids that I thought would have averted the bird. But from its vantage point outside, I could see the window was filled with a glare reflecting the mountains and trees and sky behind. And the goshawk had been flying like a line-drive baseball after a sparrow. Days and weeks later, the goshawk’s scarlet boring ferocity still flashed in memory. The bird had dared me to underestimate her, and had defied the neck-breaking brick and glass of humanity, and had flown off above the house and trees and everything into its freedom sky. The red-headed house finch was not so fortunate. She landed on the arborvitae, on the bird netting wrapped around, and became irretrievably enmeshed, dying before I knew, before I could scoop her out and set her free.

(Photo from Flickr.com and used pursuant to the fair use doctrine.)

Courage at Twilight: Do I?

“Close these blinds, will you?” Mom asked. Her habit has always been to stand, lean over her recliner, and push the slats closed with an old wooden yardstick. But now she waits for me to stand up from the couch or to enter the room, and asks me to do little things she no longer feels like doing. “Bring your Dad’s medicine, will you?” “Put your Dad’s checkbook in his office, will you?” My opinion is that I should not being doing for her things she is perfectly capable of doing for herself. Do I draw that boundary and risk hurting her feelings? No, I guess not, at least not tonight. Dad takes his turn, too: “Lucille, would you get my checkbook from my office?” I interpret “Lucille” as meaning “Lucille, Roger, anyone?” It is true that Dad obtaining the checkbook (or anything else) for himself is nearly impossible. “Your hair is beautiful,” Mom called to me after I delivered the checkbook to Dad. “That’s not possible, Mom,” I hissed. “I don’t have any hair.” She guffawed, “Yes, you do! And anyway, it’s the shape of your head that’s beautiful. I just love the shape of your head.” She cannot see my eyes rolling inside that beautiful hairless head, or my jaw muscles working in my face, or the energy it takes for me not to growl and bark. More and more I’m her perfect first-begotten bald baby boy in some weird Benjamin Button skit. On the counter lay a bag of moldy bread, which I threw into the kitchen garbage can. Throwing something else away later in the evening, I noticed the moldy loaf but not the plastic bag. Mom had salvaged the bread bag to recycle at Smith’s grocery with the blue newspaper bags and the brown shopping sacs and packing bubble-wrap and various other bits of bag plastic. Another day I discarded several mold farms growing on the forgotten cheese inside quart-size baggies hiding at the bottom of the cheese bin. And again I later found the molding cheese swimming bagless in the garbage can. Do I tell her how insulting it feels to have an old lady following after me and digging in my garbage, implying I should not have thrown this and that away, that I ought to be a more diligent recycler, that I should do things differently? Do I tell her Smith’s grocery does not want our moldy bread and cheese bags, our greasy leftover pizza zip-locks, our frozen vegetable bags? Do I point out how many gallons of heated treated water she uses to wash the bags out with dish detergent, the cost of the water far outweighing the damage of a sandwich baggie in the city dump? Do I tell her how annoying it is having all these wet washed baggies doing their damn best to dry scattered on the kitchen counters? Do I tell her the moldy cheese bag was in the garbage because I wanted it in the garbage, not because I’m lazy or apathetic or belligerent? I guess not. It should be easy for me to swallow that much pride, to let an old lady have her little quirks, for Mom to be cheered at the thought of helping to rescue the planet from plastic. I have drawn the line, however, at the gallon-size baggies that held raw chicken and raw fish and raw beef. “Mom. It’s just not possible to sanitize them,” I insisted. “Smith’s doesn’t want our raw-meat bags. Nobody wants them. And we might kill some innocent store clerk with salmonella-infested bags.” She reluctantly agreed to leave the raw meat bags where they belong, in the trash can, her feelings mostly intact.

Courage at Twilight: Spring Rolls

“Will I see you tomorrow?” Mom asked as I turned toward the stairs and bed. I stared at her, uncomprehending. “You see me—every day—after work,” I finally stammered out, and she could tell from my tone I thought she had done something bad, though she could not fathom what and muttered I’m sorry, and I felt bad that she felt bad that I might be annoyed, and assured her I would see her tomorrow. When I brought vegetable spring rolls home from Costco, she cheered with both arms raised, “Spring Rolls!” and Dad quipped pleasantly, “Spring rolls is her middle name.” Dorothy Lucille Spring Roll Baker, I thought with a chuckle, and then said the name aloud: “Dorothy Lucille Spring Roll Baker. Has a nice ring.” She laughed nervously, not sure if I were making fun, but hoping I wasn’t, and thinking I probably wasn’t, because I never do. After displaying the various prepared meals I had purchased for those days I do not feel like cooking, I stacked the boxes and headed for the basement stairs and fridge. “Don’t fall down the stairs,” Dad called after me, and I stopped in my tracks, uncomprehending. Not wanting to challenge or enjoin or even demure, I called back cheerfully, “Thanks Dad. I won’t fall down the stairs.” My reaction was less humoring when, attending an out-of-town conference, I received an email from Mom, “Hi dear Roger, Your dad wanted me to email you that he is afraid for you to go hiking somewhere where you could fall over the edge of the trail. He wants you to be careful to not go where the trail might be high up and too close to the edge of a cliff where you might fall. He was worried about you and wanted me to tell you that immediately!” I scowled at the computer screen and email after a long walk on a flat paved urban trail, uncomprehending. And I sighed. Like I often do when dinner is almost cooked after an hour in the kitchen: a long loud sigh. Dad’s hearing is deteriorating. I visited Erek the audiologist to have Dad’s hearing aids checked—they were working fine—and he offered kindly to come to the house to clean Dad’s ears and check his hearing. I gawked, astonished and uncomprehending, as Erek slowly pulled a three-inch string of wax from one ear, certain what I was seeing was impossible. No wonder Dad could not hear. The hearing test confirmed that Dad had “severe hearing loss,” no doubt due to his early unprotected years working the house-size ore tumblers at the Utah Copper smelter. Erek offered to purchase a pair of high-quality hearing aids for a reasonable price, through his physician’s group manufacturer discount. “You will hear lightyears better,” Erek promised, and my brain strained at applying a photonic analogy to ears and hearing. I decided “lightyears” simply meant “lots and lots,” and let the teaser go. Though Dad cannot hear me from three feet away, he can hear me sighing from thirty feet away, and without fail calls out to me, in a kindly tone, “How are you doing, Rog?” And he praises the meal as a “once in a lifetime best in the universe dinner.” I will keep shouting until his AGX Omnia 7s arrive, after which Dad should hear my conversational tone. I hope so. “Good-night Mom and Dad,” I yelled. “Knock if you need anything. See you tomorrow.”

(Pictured above, a view of Snow Canyon, Utah, one of my favorite beautiful places in the world.)

Courage at Twilight: The Standard Four

Just before midnight came Mom’s anxious rapping at my bedroom door. “Can you help us? The lift won’t work, and Dad’s stuck downstairs in the chair.” Worry dripped from her sagging face. I knew instantly the trouble. Little Owen, 18 months, carries around an irresistible curiosity about buttons and switches and the wondrous things that happen when he pushes them. His favorite is the light button on my Aero Garden: he taps it rapidly and repeatedly to make the bright multi-colored LEDs flicker off and on and off and on and off and on. A toddler’s delight! A close second is the illuminated cherry red switch on the back of the stair lift chair, installed at perfect toddler height and with just the right color to attract his attention. Owen and Lila, his four-and-a-half-year-old big sister, two of my six prodigious precocious grandchildren (number seven arrives in May!), had joined Mom and Dad and me for an Easter Eve dinner of traditional Polish pirogi, homemade potato cheese dumplings, expertly fashioned by their generous mother. Lila’s first and familiar impulse was to pull out the old wooden blocks Mom and Dad brought back from Brazil, dump out the box of dominoes, lay out Connect Four, and spill the enormous tote of Legos, the standard four go-to great-grandchildren games, which she invited me irresistibly to play with her. Dinner segued into the hunt for plastic eggs filled with chocolate eggs and jelly bean eggs and malt ball eggs. At age four, Lila knew exactly what to do, and chased out the not-so-inconspicuous bright ovals. Owen, at just one, gripped one colorful egg in each hand, dancing thrilled and contended with his prizes. Mom and Dad watched on from their respective arm chair and wheelchair, wearing the peaceful smiles of the gentle joy of young posterity. “We just love having you here, Brian,” Dad called as the little family bundled out the door at evening’s end for the long drive to Stockton. And sure enough, Owen’s last curious-child deed was to switch the red toggle to “off.” Mom had completely forgotten her panic of a month ago when the lift would not work, from precisely the same guileless cause. I flipped the red switch, and, with Mom feeling much relieved, up Dad rode to his bed.

Courage at Twilight: Lithium-ion

As I walked through the front door after work, Mom approached me with a written list of five things she needed help with. 1a) Dad’s printer would not work. She was right. I unplugged it and re-plugged it in, and it worked, but she had clicked the “Print” icon so many times that the resulting print jobs drained the ink dry. 1b) Replace the ink in Dad’s printer. 2) Dad’s gabapentin was about to run out, with no refills, so would I call the prescribing doctor to renew the prescription. I texted the hospice nurse, who had the medicine delivered to the house. 3) Dad’s glucometer stopped working, so would I go to Walgreens or somewhere and buy him another one—suddenly, after years of not testing his blood glucose levels, he wants to start testing his blood glucose levels, at age 88. I plugged the glucometer into my computer to recharge the battery as I wrote, and announced heroically that we would not need to buy a new one. “It has rechargeable batteries! Isn’t that amazing?” 4) Review the list of distributees for Sarah’s tribute book, which at 52 pages, including 12 color pages, would cost $12.25 a book to copy and bind. We cut the list of essential persons “who would still want to have the book in 50 years” (I suggested to him that no one would still want the book, or perhaps even be alive, in 50 years) from 60 copies to 40 copies, with the reassurance we could print more, if needed. 5) Write on the calendar the coming weekend’s activities. As Mom confronted me with the list, I asked a bit testily if I could pee first, because I had drunk too much passion-fruit-flavored ice water before leaving the office, and peeing was my first priority. Relieved, I set about the tasks, still in my hat and tie. Mom invited me to look in Dad’s office at how she had rearranged Dad’s power tool batteries and their chargers. Dad had kept her awake the night before repeating suddenly anxious expressions about the lithium-ion batteries shelved in his office closet—shelved by me, already responding to his anxieties about the batteries touching each other or their chargers and starting a 1200-degree F fire that would burn the house down, shelved by me alternating the chargers and the batteries, nothing touching anything else, with the tools far away in the garage. But he had forgotten, and had begun to panic again about lithium-ion infernos, and after midnight had sent Mom downstairs in her nightgown to redistribute the chargers and batteries more safely, so there was no chance they would touch. My completed or in motion, I examine with some confusion the closet shelf, now bare of batteries, and looked toward Dad’s L-shaped desks to see the chargers and batteries spaced there at distances of three feet each from the other. “Looks great, Mom. They’re certainly not touching each other. Nothing to worry about.”

Courage at Twilight: Welcome Home, Roger

Though Dad often cannot hear me shouting to him across the living room, he manages to hear the key turn the dead bolt, and before I have finished latching and locking the door, he is calling out to me, so cheerfully, “Rog! Welcome home, Roger! It’s good to have you home!” I’m not the brightest bulb in the box, but I’m pretty good at the light going on and showing me patterns and changes. Dad has always welcomed me pleasantly home, but his greetings have cheered and lengthened noticeable almost three years into this caregiving experience. And it is just like me to worry about the cause, and the meaning. Might he be sensing the nearing of his end, and be making an extra effort to be kind and close and grateful? Or is that just my mild paranoia? On a Saturday morning, ratchet set in hand, I set about checking all the stair lift bolts for tightness; the bolts securing the brackets to the lift structure were tight, but the bolts anchoring the same brackets to the stairs were appallingly loose, and the sound of my ratchet doubling them down reached Dad’s ears. What reached my ears was his worried complaint, “I hope he doesn’t break the lift.” Poor Mom walked into the trap as she tottered over to me and reported, “Your dad wants you to know he’s worried you’re going to break the lift,” and I barked back at her, “I don’t care. I know exactly what I’m doing.” In tears she returned to Dad and ordered him to shut up, reminding him that I was a “big boy” and knew exactly what I was doing. Of course, I soon apologized to her for barking at her, gnashing at the guileless messenger. She smiled and teared and invited me to bark at her anytime I pleased (sweet thing), to which I retorted, “Never! You deserve better.” During dinner I explained to Dad what I had done to the lift, and he smiled weakly and seemed unconcerned, and he thanked me for dinner: “Roger, we are so lucky to have you make us such beautiful, delicious food for our dinners.” All smoothed over, I guess. My New Jersey friend Bruce was his mother’s caregiver for the better part of a decade, running up the stairs at her beckoning or at the slightest unusual sound. He knows the life of sleeping with one eye and one ear open for anything out of the ordinary that might signal a need or a fall or a crisis or… My eyes feel particularly tired this evening, and I think I’ll shut them early, though part of me will be on the alert until Mom and Dad are safely in their bed after midnight. I am not a skilled caregiver, but I do live here with them and do cook and clean and fix and answer to their needful beckonings as best I can, and enjoy being welcomed home by my old mom and dad: “I’m sure glad you’re home, Roger.”

Courage at Twilight: A Pat on the Butt

Dad is mildly delighted, in the way only a crippled 88-year-old former marathoner could be, with his new used walker, painted racing red. Leaving work early to hunt for a walker, I mentioned my mission to my legal secretaries, and one reported her family had a walker they weren’t using and didn’t need, and within the hour I was driving home with the walker in my Outback hatch. With the walker cleaned and sanitized, and with the handles raised to their full height, I introduce it to Dad. “What a great-looking walker!” he chortled. “It’s a miracle!” Mom exclaimed. Well, if not a miracle, certainly a convenience and a grace. Past midnight, I stumbled to the toilet and heard Dad droning uninterrupted in his gravelly aged monotone. He seems to talk like this past midnight every night (as I stumble to the toilet), and I wondered whether he kept Mom awake or whether she simply slept through it, acclimatized by decades of droning. Back in bed for only a moment, I heard Mom utter a strange squeal, and I jumped out of bed to investigate. I stood in the dark hallway in my undergarments, poked only my head through the doorway into their bedroom, and piped up, loud enough to be heard, “Is everything okay in there?” “Oh yes,” they both called back, and Mom explained that Dad had just finished praying for them, and it was such a marvelous prayer, and show he reached over and “patted him on the butt.” She giggled over having squealed. Well, I chuckled to myself, good for you for praying and praising and being cute and cuddly and coquettish. At 4:00 a.m. when I stumbled yet again to the toilet, I looked in on Mom and Dad, lying under their blankets, back to back and softly snoring. And I remembered what kind, generous, loving, devoted people and parents they are, and how I am blessed to be theirs.

Courage at Twilight: Bad Dreams

Mom phoned me from the first floor to where I worked on the second floor: she was too dizzy to get up and prepare lunch for herself and Dad, and would I please help. It was 4:30 p.m. Dad complained at 7:00 p.m. that the bratwurst I served for dinner had upset his stomach. I gave him an antacid. Aide Jenifer texted me a photo of the bed sore on Dad’s bottom, and aide Diana texted that he almost fell getting out of the shower. Nurse Chantelle brought calmoseptine cream for the sore and ordered a corrugated cushion. Dad forgot aide Gloria’s name, and his head-crushing spells have returned. Mom cries at his complaints. And I can no longer seek Sarah’s counsel and support with a quick text or call. Every day seems to bring compounding ailments, none of them small to my elderly parents, Dad 88 years old, and Mom 84. It is what it is, and my job is simply to address the moments as they come. “I still have a huge hole inside,” he laments. To these griefs and ailments, add Dad’s worsening dreams. Last night in his dream he was with Sarah as she snowmobiled along the obscured trail, her visor snow-streaked, was with her as she left the trail and crested the berm, was with her as she hit her head against the tree, saw her lying dead in the snow, watching and feeling and being present as the terrible event unfolded and finished, helpless and bereft. He awoke and struggled to sit on the edge of his bed, where he sat until the full light of morning, afraid to lie down and go back to sleep for fear the very real dream would return. Knowing what happened is bad enough. Watching it happen is one-hundred-fold worse. Experiencing it with her was infinitely more painful. How awful, I thought, and served him with all the compassion and tenderness of which I am capable.

(Pictured above: my office credenza, with law books and portrait of Sarah.)

Courage at Twilight: Turn Up the Heat

“Is it cold in here?” Dad lobbed the question into the middle of the family room. Mom and I looked at each other and shrugged. Dad pulled his favorite soft burgundy fleece up around his neck. I moved to Mom’s kitchen desk to affix a return label to their quarterly tax return envelope, leaving the kitchen can lights in the non-blaring off position. Mom, bless her, struggled to her feet and tottered over to the kitchen, switching on the blare: “Don’t you want more light?” This is what I heard: “I know better, son, and I love you, so I’m turning on the lights you don’t think you need.” And I decided to try drawing a teeny-tiny itty-bitty boundary: “Thank you, Mom, but please don’t hover. I know how to turn the lights on, and if I wanted more light, I would turn the lights on.” “Alright, dear,” she bit, her face shrouding, and she tottered back to her chair with that arthritic hip-knee-ankle stagger. I know she had acted from a place of love, but perhaps love could have observed that I was happy in the daytime dim and trust that I will act in my own best interest, and let me be. “I’m cold. Should we turn on the fireplace?” Dad ventured from his chair. Brother-in-law Mike had come to repair the wound to the bathroom tile resulting from installing a wider door, prompting me to get in gear and calk around the door molding and frame and fill the nail holes. After two months, the project is nearly finished. “I think maybe I’ll turn on the fireplace,” said Dad, the hint growing more apparent. The night before snow fell and the temperature dipped. Dad had emailed me at work: “Roger, the weather report says a strong storm will come through this afternoon. Snow, wind, white-out conditions. They recommend persons leave work early. Dad.” It’s nice to be loved and cared for and worried over. But I am 59 years old, and am always cautious driving in snow. And, yes, when snow is coming, I leave work early. “Yep, I’m going turn on the fireplace,” and I finally took the hint and flipped the switch to ignite the gas so he could warm up. Before he had ridden down the stair lift that morning, I had heard him scream, “Owieow!!” from his shower. Mom had started the dishwasher, which diverted alternatingly scalding and freezing water from his shower stream. “I’m scalded,” he complained an hour later. “My skin is still red and sore.” And mom promised not to run the dishwasher in the mornings anymore. Sometimes it can be hard to get the temperature of things just right. The fireplace burned with yellow flame, and the fan coursed hot air into the family room. “Is it hot in here?” Dad lobbed.

Courage at Twilight: Comfort Kit

“How was traffic?” Heavy. “How were the roads?” Dry. “Was it hard to drive in the snow?” There was no snow, Mom—the roads were dry. “Did you get to see Paul today?” Yep—every day. I work with my close friend the City Engineer every day. For dinner, I served mini pizzas made from toasted English muffins topped with spaghetti sauce, chopped ham, and shredded Mexican blend cheese—a passable dinner—I have come a long way from my fine French entrees. Dad has stopped taking the diuretic medicine because he grew tired of having to pee every hour (with the benefit of increased exercise), but his legs look like fleshy tree trunks and his feet like hot water bottles with stubby toes. Nurse Chanetelle convinced him to wear his calf-length compression socks (he will not even talk about wearing the hip-length ones), and I dug them out of his sock drawer and laid then over the back of his bedroom sofa, where remain two days later. The Christmas tree came down on New Years Day, leaving a green mess of fake needles, so the vacuum cleaner came out and sucked up the needles and the bits of dried food from Christmas Eve, leaving the food and foot stains behind, so the spot cleaner squirted and the carpet shampooer roared and roamed and sucked up dark water. I take pride in my work, and left the dining and living rooms with beautiful rows of long triangular shapes, each width equal to the others. Looks so much better, I thought with tired satisfaction, and while I was stowing the vacuum and shampooer and bottles of carpet soap Mom tottered across the wet carpet with her new dig-your-toes-in gait to put the crystal candlesticks away. I suppose I am being silly, but I felt like someone had left prints in my new smoothed cement or dragged their fingers across my finished canvas. No harm done, actually—none to justify my irritation. Mom dug into the garbage to remove the mug I had thrown away, because the microwaved chocolate cake mix was gross and would take three gallons of water to wash out, and we don’t need another nondescript mug in the cupboards anyway—you see, I did have my justifying reasons for throwing the mug away, and then there are my used Ziploc bags which she pulls out of the garbage to wash with a gallon of water each and to dry over wooden spoon handles lined on the countertop, for recycling, even where they had contained raw chicken or fish—They don’t want our soiled baggies, I wanted to scream. She has been such a dedicated recycler. She has been such a dedicated mother. Her dementia is worsening. The pharmacy delivered a hospice Comfort Kit (also known as an emergency kit) and nurse Jonathan spread the contents out on the table and explained that the dozen blue oral-solution morphine micro-dose syringes are for pain or distress or discomfort or difficulty breathing (from congestive heart failure) and the dozen green oral-solution lorazepam syringes are for anxiety and distress, and they could be used together. “I prefer not to take anything habit-forming,” Dad rebuffed, smiling righteously. I want a Comfort Kit!! I felt like shouting. I could use a little morphine now and again! Another form of comfort came in Gaylen the hospice chaplain, who found Dad in great spirits and relatively great shape considering most of the people Gaylen counsels and comforts are days from death and cannot speak and do not know who anyone is and are wasted and broken and ready to go, so he assures them the afterlife is real and they have nothing to fear on the other side, where they will be free of their pains and troubles. I wouldn’t mind a little of that comfort, too.

(Pictured above: Crossing over the suspension bridge on the Bonneville Shoreline Trail in Draper, Utah.)

Courage at Twilight: Gift Dispenser

“The doctor wants to see him in person,” the receptionist asserted, and this after Sarah, and then I, more than once each, had explained how delivering Dad to the doctor’s office was not only an impossible physical feat, but also an unsafe one, both for Dad and for me, for the sheer physical strain, and how leaving the doctor’s office after an in-person visit would find Dad worse off than when he arrived, and how is that in the patient’s best interest. She said, again, that she would talk with the doctor, who on the day of the video appointment commented on how well the five-minute visit had gone, and let’s do it again in two weeks to check on the diuretic. A nurse had come to the house to take Dad’s vital signs (based upon which he is healthier than I am) the mornings of the video appointments. My goodness—so much happening today. Cecilia helped Dad for the last time, said she wished we could have worked things out with Arosa, said she might leave Arosa because the new rates are driving patients away and reducing her hours and her pay, said good-bye and said good luck and drove away. Chantelle and Liz, the hospice nurse and social worker, came for Dad’s hospice intake interview and paperwork. Dad got stuck on the “blue sheet” and what mechanical measures he did and did not want taken to unnaturally prolong his life if he had a stroke or a heart attack or a bad fall—he wants to live, damn it, not be given up on. But doctors have explained to him how cardio-pulmonary resuscitation on his 88-year-old frame would leave him crushed and bruised and brain damaged and with a quality of life reduced to an oxymoronic noun (like “shit”) that “quality” would not describe. Q: How are you feeling? A: Like great shit. We will come back to the blue sheet another day. And we will come back another day to the long medications list, and the question of which prescription drugs he might dispense with in light of the hospice goal to maintain comfort rather than artificially extend life. Mom and Dad each sat in their recliners during the long interview, and I sat in between them, moderating questions and answers, careful to let them answer what they could before jumping in, careful to quietly correct dementia’s inaccuracies, and a few downright lies, as to dates and weights and numbers and names. I sat between them, just as I did on Christmas day when they opened the gifts their children had delivered, from where I dispensed one gift to Mom on my right and one gift to Dad on my left, from their respective gift piles, identifying whom the gifts were from, keeping a written list, and moving the unwrapped gifts to new respective piles, gathering and crumpling the wrapping paper after each unveiling. (Wrapping paper is recyclable, I researched, so long as it stays compressed and crumpled when compressed and crumpled, meaning it is really paper instead of mixed with plastic or metal or cloth fibers.) Fuzzy slippers, fuzzy socks, biographies of the Fonz and Captain Picard, pounds of chocolates, word puzzle books, Horatio Hornblower DVDs, needlepoint kits, and signed cards. Mom held up her hands for her gifts, as she does with her dinner plates, like an eager chick. As the hospice women left, instant new friends, Mom announced they would each receive an Afton hug, a full-bodied arm-wrapping embrace with dancing left and dancing right, named after a beloved granddaughter. I felt mortified and turned away from the tender bizarre scene, all my inhibitions overwhelmed, but Chantelle and Liz laughed and joined heartily in.

Courage at Twilight: Tasting Sweetness

.jpg?cb=e02f4292c12968152772b21e2d446c3b&w=1200)

Dare I dip my toe again into the dark eddies, and launch into the currents of this memoir of living with the dying? My resolve to navigate these waters began before I embarked, and the eight hundred and seventy-fourth day is no time to beach. Arosa raised Dad’s in-home care rates by 75%, charging a “premium” for clients who receive less than four hours of care per day—Dad receives two—but I perceive the premium as a penalty, and the company as preying on the most vulnerable. Continue reading

Courage at Twilight: I Know What I’m Doing