We all believed it, my mother and sisters and I, that my father clung to his last heartbeats and breaths until Steven could arrive to bid farewell. We enthusiastically expressed our belief to Steven and to each other. Whether factual or no, we wanted to believe it; we wanted this mystic affirmation of a narrow sliver of hope in the midst of death. Indeed, that Steven arrived before his father’s death seemed miraculous, despite the coma and death rattle. But I soon discerned the unfairness to Steven of this testimony, which required of him wonder and faith in the face of haggard death, which broached the unanswerable question of why our father’s lucidity could not have been prolonged a mere 36 hours to allow a two-way farewell, which raised the painful reality of this last good-bye. So, I kept my belief, or my wanting to belief, silent, and sought merely to accept the circumstances we were given and to find satisfaction in having done our best with them. Steven’s trip was planned months before, but he arrived just prior to our father’s passing and left just following the funeral. After our father’s passing and our family prayer, when our small assemblage felt ready, I called the on-call hospice nurse, Monica, to report the death: Tuesday January 14 at 11:03 p.m. The official time of death, however, became the time of her certification of death: Wednesday January 15 at 00:26 a.m. She performed her coroner’s functions, wasted the remaining morphine (mixing with dish detergent and pouring down the sink drain), and called the funeral home. At about 2 a.m., the mortician rang the doorbell, bowed at the waste, expressed his condolences for our loss, entered the house, crossed the room to our mother, and delivered to her a very-long-stemmed red rose, bowing again and whispering again his condolences, which he repeated at a higher volume after Mom said, “What’s that?” After speaking comforts, he and his junior associate, dressed in black suits and burgundy bow ties, shrouded our father in white and transferred him to a wheeled gurney, where they enclosed our father’s body in a blue velvet bag with a sturdy brass zipper, and draped the whole with a blue patchwork quilt, a nice touch I did not anticipate but appreciated. And then they rolled our father’s body away and out the front door and down my wood ramps and into their Larkin van.

Tag Archives: Essay

Courage at Twilight: I Will Not Let Him Drown

For two days family members have trickled in to visit with each other and to tell my father they love and admire and appreciate him, and to say good-bye. Those living farther away video called to do the same. But my father has been in a coma. Today he has begun to show the signs of death: a rising core temperature (at times 104 degrees F); cooling extremities; sweating and clamminess; inability to swallow (he has not eaten or drunk for six days); healthy color fading to cadaver gray; producing very little, very dark urine; not registering pain or reacting to any stimuli; gurgling on liquid in his lungs; no bowel movements. The day was calm and filled with tender expressions, and I imagined he would slip away quietly into death, his body and mind finally shutting down. The rattling and gurgling in his ragged breathing seemed to worsen. I learned later this breathing is called the “death rattle.” Finishing the hundredth phone call of the day, I could hear from across the house a concerning increase in the raggedness of his breathing, and hurried to his side, where I was horrified to find his mouth filled with a thick creamy liquid. How is he even breathing through all this goo? was my first thought, quickly followed by a frantic He’s going to drown!” I remembered seeing a rubber bulb used to suck a sick baby’s nose, and ran to retrieve it. He might be on the verge of death, but he would not meet his death by drowning, not while I was here to do something about it. Please, God, help me know what to do. Somehow, my father was managing to convulsively breath despite the liquid, and I set to sucking it out with the bulb, squeezing the contents out onto a sheet. Please, God, help me to keep him alive until Steven gets here. Ten panicked squeezes, twenty frantic squeezes, fifty fearful squeezes with the bulb. My hand began to ache, and the phlegm piled up on the sheet. His mouth now clear, I called the on-call hospice nurse, who explained the goop was a normal accumulation of mucous in an unconscious person with congestive heart failure who could no longer swallow. I felt chagrined, that this were so normal, why did a hospice nurse not tell me to watch for it, prepare me to deal with it? She ordered the delivery of a suction machine. The motor suction wand helped me remove more mucous, though much of the underwater gurgling lay deeper in his throat where I was afraid to jam the wand. While he could no longer swallow, he could also no longer gag, and I probed as aggressively as I dared to clear his throat of phlegm. I did not want to injury him or cause him pain. My sister Carolyn took over suction duty while I raced to the airport to get my brother Steven, about to arrive from North Carolina on a trip planned months previous. I apprised him of the condition in which he would see his father, hoping to soften the experience. He stood over Dad, offering his silent and whispered good-byes. Carolyn, Steven, and I began to plan the night, resolving on hourly suction shifts. I would take 11 p.m., midnight, and 1 a.m.; Carolyn would take 2, 3, and 4 a.m.; Steven 5, 6, and 7 a.m.; and I would resume at 8:00. At 11:01 p.m., as I wrote this entry, pushing one minute past my shift start-time (what harm could one measly minute do?), Carolyn came to my room and whispered that our father’s breathing had changed, had calmed and slowed. We descended the stairs and found our father not breathing at all. I cleaned his face of the last thrown-up mucous and felt for breath and stared for a moving chest, but all I saw were slack muscles and a ghostly greening face. I ran for Steven, and Carolyn ran for Mom, who descended the staircase slowly on the lift in her long white cotton nightgown. We stood around our father and husband, not quite believing he was gone, his body still hot, his body unmoving, his body covered with a white flannel sheet stenciled with blue sheep. Peace and tenderness and loss and relief and sadness permeated our own bodies, together with the one last unexpected trauma of preventing his drowning, and we said nothing until I somehow knew I need to say something, not just anything, but something sublime and holy and apropos, so I offered to pray, and I thanked God for this great man, this powerful intellect, this generous heart, thanked God for giving him to us, thanked God for having each other, thanked God for ending my father’s years of daily suffering, thanked God for a family filled with love and devotion for one another. And we let him go.

Courage at Twilight: What Will the Morning Bring?

I expected this entry to begin and end with “Dad is dead.” The night before, I turned off all the lights except for my father’s night light, a small wild-wood lamp made by my son Hyrum, and said good-night to my unconscious father who lay in the lamp’s low glow. After sunrise, I lay awake in bed with a tired father’s Christmas-like morning mix of anticipation and dread, sneaking down the stairs ahead of the children for one last check on the piles of gifts before the onslaught of squeals and flying paper, in this case ahead of my mother, in this case for one last check on my father, who I anticipated finding cold and dead. But, again, he defied my expectations of certain life’s end to flicker his eyelids and responded “Hi Rog” to my good-morning greeting. The vivid yellow urine of yesterday dripped an angry opaque red. Rosie said the red could be blood from the catheter insertion, but more likely meant failing kidneys. He drank nothing yesterday, after all. I swabbed his dry open mouth with a wet sponge-on-a-stick. I smoothed Vaseline on his flaking lips. I syringed a small dose of morphine in advance of the CNA roughing him up with rolling and changing and bathing and rubbing. From the kitchen sink I heard him mumbling, and I hurried back for him to look at me sleepily and exhort me to “Be good, Rog. Be good.” I will, father, as if I know to do anything else. Then I settled in to do what any other normal land-of-the-not-dead person does: I washed last night’s soaking pots and pans, and I set the garbage and recycling cans at the curb. Mom asked me to pray with her last night, asked me to pray with her every night. But what she really wanted was to tell me that she wants to stay in the house and not go to an assisted living facility after my father dies. I told her there was no reason not to stay at home if she were healthy and mobile. But I told her that I could not be her companion or comforter, that she would mostly be alone. She liked being alone, she said, doing her simple activities, she said, her needlepointes and word puzzles. I did not talk with her about what my own life might have in store. It’s too soon. The time for that will come, but is not today.

Courage at Twilight: Sweet Moments

The family starting calling and coming over, and undeniably sweet moments began to surround Dad and to fill the house. My sister Megan leaned over him, in tears, and gently wiped his cheeks and chin and brow, talking sweetly to him, and he awoke enough for several lucid minutes of whispered conversation as she related old memories of growing up in New Jersey. When he slipped back into unconsciousness, she summarized to him some of the more interesting stories in the day’s New York Times. Niece Afton stood by and rubbed his arms for an hour and sang to him his favorite family song, “Sweetheart of the Rockies.” My son Caleb spoke out with “Love you, Grandpa!” and Dad’s eyes fluttered and he whispered back, “Love you, too.” Caleb joined his siblings on a Messenger call, and they all took turns saying good-bye, or to wave and cry. Rosie and Veronica, two CNAs, deftly rolled him over and back in order to install a draw sheet, disposable chucks (pads), and a new brief, and swabbed his mouth with a wet sponge, and installed pillows beneath his calves to keep his heels off the mattress to avoid pressure sores. My daughter Erin expressed her love and sadness from the other side of planet Earth, and my sister Jeanette and her husband Craig and Dad’s brother Bill called me to tell me they loved me and appreciated my efforts and pledged their support. Friends Ana and Solange sang Brazilian lullabies to him, and Ana told me how she had the strongest impression when entering the house that Sarah, who died exactly a year before, was there in the house with us, with Dad, along with other loving spirits—Ana could feel their presence so strongly—and how their presence remained until just after the CNAs had finished caring for Dad and Dad had finished crying out in pain as they rolled him to and fro and we had given him more lorazepam and morphine to ease his pain and anxiety and he slipped into soft snores—then Sarah left. And I told Ana I was glad she could feel such beautiful mystical things and tell me about them because I am both utterly empty and completely saturated and can feel nothing but only flow from one task to the next to the next—there are so many tasks—and in between I can but withdraw into myself and sit curled up in an emotional corner unable and unwilling and unready to feel. The last person awake in the house, I looked at Dad in the nightlight glow and knew he was dying and would be dead within hours and saw his passing as just another fact among an infinity of sterile facts, like the ripening of the green bananas, like making mashed potatoes and sausages so I had something useful to do, like the glow of the reading lamp and the squeak of the rocking chair, and Megan’s teary eyes, and Mom’s veneer of cheer thinly covering a universe of grief and fear, and the stars shining coldly in the winter sky.

Courage at Twilight: Bedbound

I had hoped Dad’s mental acuity would return after a solid sleep, if not some of his physical strength. But his first utterances upon waking were incoherent nonsensical sentences, spoken with a thick tongue and loose jaw. His beloved Gloria came to take care of him, the day being Sunday, and he broke her heart calling her Martha and Ana. “Nelson, I’m Gloria!” she nearly wept. He strained to sit up so he could pee, but had a distorted sense of himself and his surroundings, holding the urinal absently in one hand while peeing on the bed and on the floor. She laid him back on the bed and helped him finish, then stripped and remade the bed around him. He did not want to wear a brief, but we put one on anyway, explaining that it was necessary because he had no strength to use the urinal or the toilet. Gloria and I sat at the kitchen table and faced the reality that my father and her Nelson was in serious shape, would be permanently bedbound, and we would need to reevaluate the whole procedure for his care. He adamantly opposed staying in his hospital bed in the corner of his office, so I slid away his recliner and we rolled him in his hospital bed into the recliner space, comforting him that this way he would be with Lucille and listen to her music and watch her TV programs and eat lunch together just like normal. I reported to Jessica that Dad’s condition had deteriorated quickly and severely, and that he needed a catheter because he could not manage urination in any manner. She was shocked at his appearance less than 24 hours after her previous visit. She observed his incoherence, his exhaustion, his inability to swallow a pill, his breathing and speech and loss of appetite and distorted sense of himself and his surroundings. “I wonder if he had a heart attack yesterday when I was here,” she said. Even one day before, convincing him to accept a catheter would have been impossible, whereas today he did not resist or complain, and the bag quickly filled. Though he awoke for an hour as Gloria bathed him and changed his bedding, he had been confused and incoherent, and, with the catheter in place, he now slipped into an all-day sleep. We tried to feed him pinches of food, but he could not chew or swallow. When we gave him his pills, he alternately held them in his hand, dropped them into the cup, and chewed them without water. We gave him water to wash the pills down, but he aspirated and sputtered and coughed and his breathing gurgled during his hours of sleep. I asked if he were in pain and he shook his head no. I asked him other questions but he did not respond. He ate nothing. He drank nothing. He took no medications. After observing him, Jessica thought he would not survive the day, that he was beginning to transition from life to death. She suggested I call the family and invite them to say their good-byes.

Courage at Twilight: Almost Comical

Jessica, the on-call hospice nurse, arrived just in time to see Dad lurch into an episode of unendurable chest and rib pain. His vitals were good, she said, suggesting the episode was not a heart attack, and authorizing me to give four 0.25 ml morphine syringes, plus a 0.5 lorazepam syringe (“they work better together”). After an hour, the pain suddenly let up, and he settled into a snoring sleep. He stirred at intervals, waking slightly, but not fully, mumbling gibberish, making incomprehensible nonsensical conversation. At bedtime, he could not sit up, let alone stand up, and I could see clearly the impossibility of getting him to bed. But I needed to get him to bed, to confine the mess, the increase his comfort, and mostly because I suspected that once in bed he might never leave bed again alive, and that if I did not get him into bed this night I would not be able to thereafter because of his utter weakness and my insufficient strength. He struggled to lean forward, but explained with hand motions the mechanics of how he would simply stand up and turn clockwise to sit on the walker seat, his voice strangely thick and dull and slurred, his self-perception skewed and delusional. How would I get him up and out of his recliner and convey him to bed? I wondered. I could not fathom how. Following our routine–we had to try–I hooked an elbow under his good right shoulder (the left side continued to pain him terribly) and carefully lifted, while mom lifted with her hands under his butt—and all we succeeded in doing was scooting him dangerously close to the edge of the seat, within an inch of sliding irretrievably to the floor. An idea came, and I hurried to executed it. Phase 1 involved leaning his torso back, lifting his legs, jamming the walker seat against the recliner seat, holding the walker in place with my foot, and dangling his legs across the walker seat. With a broad, two-handled sling, I sat him up and shimmied him from the chair and onto the walker seat, bumping his butt over a gap. The maneuver worked, and he sat nicely on the walker seat. As I held him upright with the sling, Mom and I managed to roll the walker backwards to the hospital bed, which I lowered as far as it would go. Phase 2 involved leaning his torso back onto the bed, with the sling behind his back and under his arms. Mom lifted his feet clear of the walker, and I stood on top of the bed leaning over him, my feet sinking deeply into the mattress. I heaved with my legs and arms—trying not to strain my back—to slide him in six-inch intervals onto the bed, but perpendicular to the bed, then used the same maneuver to turn him parallel and to slide his head toward the headboard. With each heave, his head slid backward between my feet as I stood over him on the bed. At any point, this slapstick performance could have gone terribly wrong, with Dad crashing to the floor, with my desiccated spinal discs shattering, with me tumbling off the bed, with only half of his body in bed and half out…. But for the tragedy of Dad’s situation, and maybe in spite of it, any observer would have laughed hysterically at our antics. Somehow, with just the right forces and angles and frictions and strengths and moves, we succeeded. I would not want to have to do it again, and now that Dad was correctly installed in his bed, I likely would never have to. He had cried out in pain throughout, and he eagerly accepted the morphine he had rejected for the previous 13 months, and quickly settled into sleep, a sleep from which he never fully awoke.

(Photo copywrite by Caleb Baker.)

Courage at Twilight: Unspoken Apology

Before I understood Dad’s pain, he shouted at me as I lifted gently under his left arm to help him stand and turn for bed, and I shouted back at him to not shout at me, making sure to shout louder than he. Lying panting in his bed, he explained the horrible pain he was having in his chest. Understanding his pain helped me find more compassion and patience, helped reduce my resentment, helped me speak softly and forgivingly, and I thought in the night of the apology I would offer him the next morning. I’m sorry I shouted at you, Dad. Can explain something to you? Just let me get through it, and then you can respond. I have always felt afraid of you and intimidated by you. You were always so smart and so strong and so successful, a superstar to so many, and I wanted to be all you are but knew I would never be. I have always wanted to make you proud, but you never told me you were proud of me. I have always wanted your love, but you never told me you loved me. I always felt afraid of your disapproval and disappointment. And so, I feel destroyed and annihilated when you shout at me or become angry or disappointed with me. And now, at age 60, I shout back or become defensive, only to stay alive. Always in my life I have shrunk to be as small as possible, I have shrunk into shame, I have sunk into depression, for I am a man who has depression. But, I don’t want to die, Dad, and to not die when you are disgusted with me or disappointed with me or angry with me, I fought back. That’s what is happening. I’m trying to survive, to stay alive, to not die. But I can see that you weren’t angry with me last night; you were in severe physical pain, and so I apologize to you for shouting back at you when you shouted at me, because you really weren’t shouting, you were just crying out in pain. I’m sorry. But in the morning, I found him too feeble and in pain and ashen-faced and miserable and weakened, and could not bring myself to add to his suffocating burdens. My apology may have brought understanding, but would have added to his heaviness and suffering. Instead, I listened to his troubles and called for the hospice nurse to come, on a Sunday, and administered the morphine, and did what I could to safeguard his comfort.

(Pictured: boot hill grave in Peoche NV, the small mining town of my father Nelson’s grandfather Nelson.)

Courage at Twilight: Cracked Ribs?

Wishing Dad good luck for a good sleep did not work. He awoke with pains that seared and branded and made him cry out when he adjusted in bed, pains that worsened over the next day, pains he hissed ashen-faced that he could not deal with, pains that made him cry out and shout when helping him move to the toilet or to bed. He thinks he cracked a rib when I used the gate belt after he fell, to bring him his hands and knees, and then up to the toilet seat. Jessica, the on-call hospice nurse, tells me over the phone to give him a 0.25 ml oral morphine syringe from his E-kit to see if it helps with his pain, and then another syringe if it does not. I will do that, I say, and I ask her to come to the house anyway, on a Saturday, to hear directly from him what he is experiencing so I do not bear the burden of correct translation. We could take him to the hospital for an x-ray, but the experience of pain and exhaustion of getting him there and undergoing the procedure would bring no gain: there is no treatment for a cracked rib but weeks of rest and pain management. I cracked four ribs several years ago in a mountain biking crash, and I well remember the weeks of agonizing searing pain, and how grateful I was for oxycodone, without which I would not have slept, the more so because a week after my wreck I camped for three weeks with 34 boy scouts at the National Jamboree, a trip two years in the making. So, he will try the morphine. And he reported that the 0.25 ml dose did dull his pain, but was bitter-tasting, made him drowsy, made his body tingle, and caused some nausea. But it did dull his pain. This dosage, or even double, he can safely take for pain every hour, says Jessica. She will have a fresh supply of morphine sent over, which is much easier to obtain for a patient on hospice than not, she says. I felt relieved the low dosage helped. He, too, felt relieved, from the worst of the pain, and was grateful.

(Pictured: Boot Hill grave marker in Peoche NV, the mining town of my father’s grandfather.)

Courage at Twilight: Caregiver Blues

Despite my instructions, the new hospice nurse revealed to Dad that his gift, and my reporting of the gift, got his old nurse fired. I called Kourtney and expressed my utter dismay at being put at this new squeezing fulcrum point, this point of carbon-to-diamond pressure, and I demanded (or desperately requested) that she visit Mom and Dad and explain—before I arrived home—to them how the termination was not Dad’s fault, how the nurse accepting the gift violated all federal, state, and company rules and ethics, and especially how the termination was not “Roger’s fault” for having done right to report a wrong, and I needed to arrive home to a place of relative safety instead of a place of shaming accusation and recrimination. After the hour-long visit, she assured me he understood and was sufficiently calm. Indeed, I found him calm, yet eager and accusing. She was fired, Roger, because you reported the gift. (I.e., you snitched.) I stiffened myself against shame, a little boy standing up to an angry giant of a man, and immediately interrupted the lie. “That is not true,” I shot back. Your nurse was fired because she played on your sympathies and committed a crime, not because I reported the crime. That the company did not know about its employee accepting an illegal gift does not excuse her and does not condemn me. But he would not relent, and I would not be shamed, and in my momentary rage I thought, You are not my father. You are the man who even on his death bed needs to be right and will tell me how I am wrong and how I am at fault even though I do the good and right thing, the hard thing, because it is good and right. You are the man who belittles his son rather than acknowledging his own shortcomings, instead of thanking his son for his courage and his ethics and his advocacy for truth and right. And, I am afraid to say, I continued spinning my mental yarn of hurt and justification. You are the man whom I have always wanted to please but could not, from whose lips I craved but never heard “I love you” and for whom my saying “I love you” feels like chewing glass. My own fears and frustrations and guilts and inadequacies continued to pour through my thoughts. You are the man around whom I strapped a gate belt and lifted with all my decrepit might to raise you from the floor and onto your chair and into your bed and who complained about how I had hurt you, instead of thanking me for saving your life, again. You are the man to whom I wanted to be a beloved son but to whom I instead became a resented caregiver, or a toxic mix of both. Leaving him to watch Dr. Poll alone, I resolved again never to live with my children in my future decrepitude.

(Pictured: Chicago Ivy #3.)

Courage at Twilight: A Closing Universe

“In what universe do you think this is sustainable!” I want to scream at him. Dad is lying naked on the floor, having collapsed on his one-step voyage to the portable potty. Mom had screamed “I need help with your dad!” from downstairs, and I knew before launching to the rescue that Dad was on the floor. All I can do is stare grudgingly at him, this man for whom my responsibility is to do the impossible: get him up off the floor and onto the toilet seat. “In what universe do you think we can keep doing this!” I choke back the words. Mom begs me to call this neighbor and that neighbor, and I shoot back that if I call anyone it will not be the poor neighbors, but the paramedics. His walker lies, folded, on the floor across the room to where it rolled, and from it I retrieve the gate belt sewn with four helpful handles. The first impossible part of the impossible hoisting procedure is to pass the buckle and strap under his chest, and I jam the buckle under him and haul on his shoulder and hip to roll him over enough to pull the strap through and cinch it tight around his slack once-muscled chest and above his now bulging belly. On the count of three I heave from the handles and Mom lifts and Dad pushes, and we, as a team, we manage to raise him to his hands and knees, upending my predictions. But there is no resting position for him, only multiple collapsing positions, so we move quickly into the next phase, in which he grasps the potty handles and somehow I lift his bulk enough for him to lift his knees and I wrestle his backside onto the potty seat. My silent screaming continues, now about how much I hate this experience! But I do not scream. I never scream. I never chastise or berate. I never shout. Except that one time he condescended to me for installing a wider bathroom door without his permission on the eve of his return home from the nursing home, and I instantly boiled over from quiet to rage bursting from its cage of lifelong inhibition and I pounded on the kitchen counter and I thought I had broken my hand on the stone kitchen counter, the time Sarah was a living witness, a breathing comfort to me. And now he is moving his bowels and is bossing Mom to bring him his walker because he can’t, he says, do anything without his walker right in front of him, and the bossiness is a cover for his embarrassment and powerlessness and fear. “I’m trembling, Rog. I’m so weak and shaky.” No shit, I retorted in silent and staring thought, trembling myself. I muscle him from the potty to the walker and muscle him from the walker to the bed, using hands and arms and knees, maneuvering methodically to leverage every opportunity to inch by inch transfer his bulk to his bed. The crisis is over, and I announce that I’m going to bed, and I wish him good luck for a good night’s sleep, and I take a sleeping pill.

(Pictured: ivy on my Chicago daughter’s wall.)

Courage at Twilight: I Haven’t Lost My Mind

Dad asked me to make an entry in his check registry, in which he keeps a scrawled and unnumbered untallied record of his checks. And that is where I discovered the $500 check made out to his dear hospice nurse. The image of the entry bounced erratically around my brain for hours, seeking but finding no possibility of legitimacy. I asked Mom and Dad if I could discuss something with them (“Certainly!”), explained about finding the registry entry, and asked what they could tell me anything about it. Dad offhanded the check as a simple Christmas gift, and turned back to his book. I pressed him about why this gift in this amount to this person. “I just thought she needed it,” he demurred, not looking up. I pressed further: but what did she say that led you to believe she needed money? He mumbled something about hard times and her husband being out of work, with Christmas coming. I launched, carefully, into a lecture about his days of monetary magnanimity being over, that his bank balance was low and diminishing, that giving his money away sabotaged my ability to take care of him, that my fiduciary duty to him required me to raise the subject of financial irregularities with him, and that, besides all these, his hospice nurse playing on his sympathies and accepting a gift violated hospice company policies, Medicare hospice licensure rules, and nursing ethics. What’s more, for a person in a position of trust and confidence (like a hospice nurse) with a vulnerable adult (like him) to obtain that vulnerable adult’s funds (like a $500 check), constitutes the crime of exploitation of a vulnerable adult. But I asked her if there were any rules that prevented her from accepting a gift, and she said no. Just a week earlier, Jeanette had warned Dad about another exploitative person who might ask him for money, and he had retorted that he could “recognize a con.” And yet here he had been conned. “I haven’t lost my mind,” he insisted to me, but he could see now he had been played, and he felt embarrassed. “I won’t do that again,” he promised. He looked to Mom, “We won’t do that again.” Lying in bed pondering the bizarre situation, I realized I possessed a new power, namely, the power to get the nurse fired: a power I did not want. We liked this nurse; we trusted her; she is a nice woman and a good nurse; and I did not relish reporting her and causing her pain. And that is part of the con. My sympathies were being played, too. So, I used the power I had been given: I called my contact at the hospice company and reported the occurrence of the gift. The same afternoon the company director called to tell me the gift had been investigated and confirmed, the nurse had been fired, the nurse would be referred to the Board of Nursing, and the $500 would be reimbursed. Thank you so much for calling. Sudden and severe, but not surprising. I fought to not feel responsible for the devastation just wrought in the life of the nurse and her family, due to my report, urging my brain to believe the truth that these were direct and terrible consequences of her actions, not mine. But I will not tell Dad that I reported the nurse and that she was fired, because his brain would lose the battle, and he would berate himself for giving the forbidden gift and destroying the gifted.

(Pictured: brick wall, with ivy, surrounding my daughter’s Chicago apartment back patio.)

Courage at Twilight: Nobody Cares

Ten p.m. The hated hour. The impossible hour. The hour of transfer from recliner to walker seat. The hour of rolling dragging backward to the bedroom. The hour of transfer to the edge of the bed, to enough of the edge to stay on and scoot farther in, and hopefully enough not to slide off and fall to the floor. The impossible hated hour. He doesn’t want me here, Dad doesn’t. He knows he’s poised on a precipice: “I don’t know if I can do it.” He knows some unseen stress is getting to me, that I am on edge and irritable, and has no idea it has to do with him. “Where’s Lucille?” he demanded, looking to her to lift his butt, though she can’t, pretending he doesn’t need me, though he does. “I won’t do it without Lucille.” On this night, gripping the armrests to make the impossible effort, he looked up at me in his nakedness and remarked how sixty years ago he was a student in Brazil, and I was a baby, and I dutifully observed in return what a long time ago that was. But he persisted and began rehearsing to me one of his many mystical stories, this one about being assigned to visit ten families who no longer came to church, ten families who had no phones or cars (neither did he), ten families who lived far from the church building and from each other and from him, families whom he visited every month for the school year he was there, riding buses in the vast internecines of São Paulo, urging them to Christ, inviting them to church, making the last visit as my first birthday neared, and hearing the voice of his Savior assuring him that his offering of service to the ten families had been seen and accepted. But as he began the old story, looking into my face with the earnestness of someone having something of utter importance to say that had never been said or heard in the long history of the world, I walked away, having absolutely desiccated internal emotional reserves, muttering that I had something in the oven that needed tending, and indeed I did have something in the oven, for the second time, because I had baked the miniature mincemeat pies for the first time on the wrong temperature and now I hoped to salvage them for an office party the next day. “Never mind,” he said, and he looked up at Mom imploringly: “This is important. And nobody cares.” Back from the oven, my own heat rising, I rebutted with how unfair that was to me, and how of course I cared, and how I have heard the story a dozen times and did not need to hear it again, and how I had something in the oven that needed tending, and how I had a lot going on in that moment, and how I was tired and wanted to go to bed. Another painful barefoot moment on the razor’s edge of being needed but not wanted passed, and I hung back in offering a steadying arm under his armpit until the moment just preceding a would-be fall. Somehow he made it to the edge of the bed. “Good-night, Mom and Dad.” From where I sat in the living room, piecing together the faces of angels and shepherds and sheep, I listening to his gravelly petition to his Heavenly Father, praying for me, praying that I will not be angry, that I will be blessed in my hardships, that He will be with me, totally unaware of the cause of my feelings. Placing the Jesus piece in the Nativity puzzle, I breathed, “Blessed Jesus, let me not do this to my children.” Let me leave this planet before this, knowing they will weep for a day and then get on with their joyful challenging bitter hopeful grinding lives, with me a happy memory instead of an angry silence or an endlessly repeating story of a glorious romantic mystical reinvented past.

(Pictured: my own brickwork in an antique-themed writing studio within my old chicken coop.)

Courage at Twilight: I’m Worried

Mom served Dad his can-of-soup lunch at 2:53 p.m., and he said hopefully that he hoped they didn’t have to watch the last seven minutes of Family Feud. “I don’t care what you want!” she snarled, hoping precisely to watch the last seven minutes of Family Feud. At the kitchen sink, I turned to look at her in disbelief, raising my shoulders and hands in a What was that? gesture of irritated incomprehension. None of us said a word, but she had seen me, and turned on Dr. Pol. I guess she is done being bossed by the boss, the man of the house. And now she possesses the marvelous power of the TV remote. That morning, I had driven to a temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a beautiful edifice, a place apart from the cares and worries of the world, where we dress in the symbolic equality and purity of all-white, and learn about God’s plan for humanity and about our place in the vast universe, our origin and destiny, and we make promises to be good and chaste and generous and faithful to the faith and to the Church and to our God and to each other. In the temples, we act as proxies for the departed, being baptized on their behalf, and linking them together for eternity (if they wish it) in their mortal family units as couples and as parents and children. I had come for peace, for inspiration, for answers, for a settling of the spirit. But sitting in the bright room with chiseled carpets and gold leaf wall accents and gorgeously upholstered chairs and elegant inlaid wood tables and brilliantly colored stained glass and tinkling sparkling crystal chandeliers, sitting and seeking some peace, all I could hear in my head was Dad repeating his ruminations: “I’m worried about…” (insert the name of any one of his two dozen grandchildren, of any one of his dozen CNAs, of any one of his six children, etc.) hour after hour after day after week after month, endless cogitations about endless worries, repeated to me daily, and I let his rueful expression worm into my head and crowd my heart, and I let all the worries follow me into that quiet holy place, unworthy stowaways into the temple, to churn and swirl and tense my neck and back and distract me from the hopeful joyous prayers and promises, and fill me instead with dread and angst. And when I came home and he began again with “I’m worried about…” I changed the subject, I interrupted, I dodged and demurred, I pretended I had not heard him, and I launched into another subject, a small subject, a brief subject, then made the excuse of having work to do upstairs.

(Pictured: mountain stream in Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah.)

Courage at Twilight: No Saint

Janis says to me every week at church, she says: “You are such a blessing to your parents. They are so lucky to have you.” And Stephen, whom I respect, and who knows a lot more about caregiving than I will ever know, told me, “You must have the deepest reservoirs of unconditional love. If you were Catholic, I’d nominate you for sainthood!” (Wink-face emoji.) He’d have to call me the Swearing Saint, I muttered. And my great and good friend Blake: “You are amazing…you are preparing your place in Heaven with how you are treating your parents.” Heaven, huh? Hell, more likely. Or some other type of purging Purgatory. Where the angry and resentful and rude go to cool off for a few millennia while awaiting the Final Judgment. I think I will need every one of those years. “Help me get to the potty, Lucille,” Dad instructed her. “I can’t!” she cried, at 85, barely able herself to totter about on stiff knees and hips, let alone support and swivel around his belly and buttocks. “I’m not strong enough!” Exactly so: you’re going to get her hurt, Dad, make her fall. And so I wait—sitting at the piano, standing at the sink, cleaning up the kitchen, decorating the Christmas tree, piecing together a Dowdle puzzle, writing this Courage entry—listening for the effort grunt to become the falling-panic help-me I’m-going-down grunt, waiting for “I don’t know if I can do it” as he pivots from the toilet to the chair, a rotation of 45 miserable impossible degrees. You shouldn’t be here! I want to scream. But I never scream; I just seethe. And at church, Janis rejoices, as if for the first time, as if with a novel thought, as if a newsworthy human-interest story, as if I beamed at her pretentious praise: “You are such a blessing!” Go to hell. I am no saint. No way. I’m just an angry lonely stressed exhausted resentful empty depressed anxious angry 60-year-old man waiting and waiting and waiting for the little event that will inevitably initiate the cascade toward the big end. And Stephen, rightly, accurately, justifiably, gently encouraged me to try to be less of a caregiver and more of a son. Point taken. Touché. But…I may have lost them both.

(Pictured: Stream in Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah.)

Courage at Twilight: Television Tyrant

“Is this asparagus?” Dad called out after I served him his dinner plate. “It tastes like a stick.” The only words my mind would form were profane, and I clenched my jaw against their audible escape. Perhaps he was trying to be funny? Or, perhaps his dementia really is that bad? The asparagus was very skinny, after all. But mighty tastily cooked. After the dinner-time Next Generation rerun, I retrieved the empty dinner plates—all the sticks on his plate were gone—and Mom began surfing the channels. Oh, the power. “We could watch ‘Superman’,” he suggested, catching a glimpse of the name on the screen. “No.” Mom answered simply. “We could watch ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’,” he ventured again. “NO!” she hollered. She was in total control. He was helpless, defeated, and he knew it. I fled the kitchen, weary of the too-frequent tyrannical television exchange. At 10:00 p.m., when I wanted to be in bed, I descended the stairs to the family room, the scene of a terrible nightly struggle. Dad’s task was simply to stand, to hang onto the walker handles while he turned, and to sit his bare bottom on the towel-covered walker seat. No steps required. A good thing, since he has no steps in him to take. He pushes, and he rocks, and he pushes, and he trembles, and he slowly rises from his recliner, his body bobbing convulsively from arms and legs that will no longer bear his bulk. His swollen feet shift an inch or two at a time in the 120-degree pivot. And there it was—I could see it: he was going down, and once he went down there would be nothing I could do but dial 9-1-1 and be up half the night with adrenaline and worry. So, I pressed a fist into his hip and shoved, and he groaned and slumped precisely into position and exploded angrily, “DON’T PUSH ME!” I had no patience for the petty power posturing, as if he could have positioned himself. I recognized that he was reacting to my maneuvering with the only power he had left: the attack. But I was having none of it. “DON’T YELL AT ME!” I retorted. “If it weren’t for me, you’d be on the floor!” I pulled the walker, Dad’s back toward the direction of travel, to his bedroom, his feet dragging uselessly behind, swollen and deformed. I will not give him the meager dignity of pushing the walker with him face-forward, not because I am spiteful, but because of his difficulty in inching his feet forward and my difficulty in not running over his hideous toes. So, I drag him. And I position him facing the bed for the last agonizing transfer of the day. “I don’t want any help, because I can do it myself, even though I’m slow.” Be my guest. I must be there anyway, just in case, and to spare Mom the labor and worry. And, somehow, every night, he pivots just enough to land his butt on the edge of the bed, barely. But I want to scream at him that he shouldn’t be here, at home, scaring everyone and bossing everyone and narrating the news in real time, a delayed echo competing with David Muir at volume 45, and complaining about eating sticks for dinner, and making Mom lift his butt. But, of course, he should be here: that is the whole purpose in my being here, so that he can be here, until his end. Though not wanting him to die, that purpose has exhausted me and left me angry and resentful despite my every effort to be the good, dutiful, patient, faithful son. At the Thanksgiving dinner table two days before, we sang one of our favorite family songs, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and Dad explained how it was an old slave song, the enslaved Black Americans supplicating God to send his fiery chariot to end their suffering and convey them to a merciful heaven. We have sung that song since I was a little boy, at home, around the campfire, at reunions. “One day, soon, that chariot will swing low for me,” he sighed.

(Pictured: fall leaves on an arched wooden bridge over a dry creek in Dimple Dell, Sandy, Utah.)

Courage at Twilight: Please Press Mute

Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers in 1947, played at the old Ebbets Field, and retired to see his team, Branch Rickie’s team, move with O’Malley to Los Angeles. The Yankees remained, to dominate. And in 2024 the two historic New York rivals faced each other, for the 12th time, in baseball’s World Series. Mom cranked the volume to jet-engine level, and the crowd’s roaring me pained my ears. Dad began to talk, and I could hear neither him nor the announcer, so I waved for Mom to mute the barrage. The TV remote has grown old, and certain buttons respond only to forceful fat-finger pressing, not that her fingers, or mine, are fat, but the buttons are so small as to defy precision pressure. She gives the mute button a focused, two-handed effort, leaning forward and stretching her sweatered arms toward the television: surely the closer the remote is to the appliance, the better the remote will work. “That pitch was a ball. It was low, and outside. And he swung at it, and he missed.” I nodded dully at this intelligence, already two batters old, and waved for Mom to reengage the decibels. The mute button shows signs of extreme wear, and, again, she strained to shorten the distance those struggling radio waves had to travel. It seemed to work. Dad soon began to comment again, this time on a base hit, adding his indecipherable garbling to the crowd’s screaming, and on an unexpressed pretext I exited to the kitchen, perhaps for ice cream. At the commercial break, when Mom mercifully mutes the aural chaos, I announce how tired I felt, and that I thought I would go to bed. It was the top of the ninth inning, in game 5, with the score 6-5. I still don’t know who won the game, or the series. Evenings are a bit quiet now. A bit.

(Photo from Wikipedia, used under the Fair Use Doctrine.)

Courage at Twilight: You Don’t Answer

Mom came home with a dead turtle. A cleaned and varnished carapace. Barbara had taken her for an outing to the Native American Trading Post on Redwood Road, a favorite haunt. I myself have enjoyed browsing there, bringing back southwest-themed pottery, woven wool blankets, and the heavy sense of vast peoples’ loss and pain. On this particular day, Mom struggled to choose an object of interest, bringing home the turtle shell. She placed it on the dining room table. Sarah’s headstone has been ordered, the spot marked by a temporary plaque, and I am still pissed (as in the American angry, not the British drunk). The stone will be a burgundy marble. Pissed, and attempting to carry a heavy unwieldly sense of loss and pain. Guilt compelled me to invite Mom and Dad on a walk, not having done so since Dad collapsed a month ago and lost all ability to walk. I aided him in his struggle to stand enough to transfer his weight to his walker and then to the seat of his power wheelchair, taking nary a step, his entire mortal energies consumed, burned up, in a hunching stationary pivot. I threw a towel under his bare bottom and tucked a blanket under every inch of buttocks and legs to shield his nakedness from the wider world. Now I can boast that my dad took a walk in the nude around the block. Back at home, he received the driver license division supervisor with his usual cheer. A DLD letter had arrived advising Dad to appear in person to renew his driver license. I called the DLD office and explained that Dad did not need to renew his driver license, and could not have come to the office even had he needed a driver license, but that nonetheless he would appreciate an official Utah ID card, and what could they do to help. The supervisor and a clerk came to the house with their computers and cameras and cords and got the job done. “Don’t tell anyone,” they enjoined. “People will take advantage—everyone will want us to come to their house just because they don’t feel like coming in.” We assured them their secret was safe with us. That evening, Mom sat by Dad’s hospital bed where he lay, undressed for the hassle of clothing twisting around his torso and obstructing the urinal and generally keeping him uncomfortable and frustrated and awake. Sleeping naked is simply easier. They held hands in the glow of Hyrum’s homemade wooden night light as Dad began his long gravelly prayer. “Dear Father,” he began as usual. Then my faith-filled mystic of a father surprised me. I have heard him tell dozens of stories of having heard and felt and seen the voice of his Lord instructing him on whom to bless and how. Now, he plied his God: “Father, it is strange: You tell us to pray. And You promise to answer. But You don’t answer.” He went on a long while, praying anyway for the family’s needs, but I did not stay to listen—what was the point? This is the day of Dad’s endurance. Enduring a collapsing body. Enduring a dementing mind. Enduring the aloofness of his Invisible Divine. My own faith urges upon me a mythology of God’s ever-active love and nurturing, a faith that They undergird and protect and teach and strengthen in all moments of endless time, all moments, though Their reality is inscrutable and undiscernible and vague. Ultimately, I choose to believe They exist and care—infinitely—because the alternative is insuperably sad. And I do not want to be always pissed off. The dead turtle watches over us stolidly from the dining room table.

(Pictured: Hyrum’s little wooden lamp named Joia (gem or jewel, in Portuguese), which Dad uses for a night light in his downstairs hospital bed office/bedroom.)

(Pictured: Hyrum’s little wooden lamp named Joia (gem or jewel, in Portuguese), which Dad uses for a night light in his downstairs hospital bed office/bedroom.)

Courage at Twilight: Night Lights and Shadows

“Help him pull up his pants,” Mom instructed. I responded that I would help Dad if Dad needed help, but I wasn’t going to stand there waiting for him to need me, standing and waiting for something bad to happen. “I can’t just stand there waiting to see if he needs me, hovering, waiting, waiting, worrying for the next hard thing to happen. I can’t do it anymore. I can’t.” Twenty minutes later, Dad finally needed help pulling up his pants, and I was there to help. But I hadn’t hovered and waited and worried and worn myself out over it. I have to say, I don’t care, which, of course, means I care a great deal, but am weary of the worry of caring. After three accidents the next day, Dad admitted to me that he might have to start wearing a brief. The only way he will wear a brief is if the brief idea is his idea. I don’t bother suggesting. “Whatever you think you need, Dad.” So tired, I’m often in bed by 10 p.m., and often wake up at 11 or 12 feeling hungry, or I awaken for no apparent reason. To get past the master bedroom, I must traverse the light field cast by the outlet night light, sending daddy-long-legs shadows into their room, and as Dad lies in bed rehearsing to Mom the family’s challenges and blessing, he never fails to detect my quick passage, calling out without fail, “There goes Roger down the stairs to get a snack,” and I roll my eyes in the dark. Some nights I stand at light’s edge, wondering if the snack is worth being discovered and commented on, again. This morning, Dad rose from bed and strained to stand at his walker, at 8:30, and he immediately collapsed to the floor, too weak to move. Mom was in the shower. When she discovered him lying on the floor, she put a blanket over him and waited for an hour for the CNA to arrive. She phoned no one, not even me—she said Dad would not let her call. Instead, she sat in her chair watching her husband immobile and paralyzed on the bedroom floor. At 11 a neighbor texted me, “Hi, my wife mentioned that she saw some activity at your house this morning.” Some activity? What the hell did “some activity” mean? “Some activity” meant an ambulance and a fire truck pulled up to the house with flashing lights. The paramedics and firefighters—it took five of them—managed to hoist Dad off the floor. Dad will sleep is his recliner tonight. He is too weak to get himself to the chair lift. I have set him up with large absorptive pads underneath him and on the floor, with a urinal, with a portable toilet that he likely is too weak to reach, with blankets, with his feet raised and his body laid back, and with the very real question in his mind of how he will get through the night. Well, I can’t piss for him, or stand up for him, or walk for him. I can just give him what he needs, or try to, and respond to whatever happens.

Courage at Twilight: Garden Dreams

The Facebook event, I found out, showed the wrong address and the wrong map for the tree planting activity. I searched for over an hour, growing furiously upset to an extent unusual even for me and out of proportion to the circumstance. All my focused mental strength brought me slowly to self-talk and deep breathing and prayer, and the dissipation of rage, and acceptance of the disappointment and failure. Driving home from being lost, I saw a sign for Sego Lily Gardens, and pulled in. Decorative rock covered an enormous round buried drinking water reservoir, and the waste strips and corners had been turned by the city into pleasantly meandering paths within groves of pines, and grassy gardens with blooming flowers, and creeping groundcovers. A downy woodpecker did not mind me standing only three feet beneath his piney perch as he pecked. This sudden immersion into quiet living beauty counterbalanced my earlier distress, and I felt almost grateful at having gotten lost. In these gardens, my dreams reawakened, of a pollinator garden buzzing with bees and graced by lilting butterflies, birds singing overhead, flagstone paths winding among tangled native flowers, a bench here and there. I love the beauty of Dad’s and Mom’s manicured yards and turf lawn, and I work hard to keep them immaculate. But I yearn for more natural surroundings, unmanicured and authentic, not forced into shape, but emerging from evolution’s own DNA, with some gentle shaping of garden form from me. A week later I brought Mom to the garden, and pushed her in her wheelchair around the garden paths, twice. We soaked in this suburban jewel, unknown to us before, touched by it now, feeling for the moment blessed and graced and whole.

Courage at Twilight: Noises in the Night

Bowing to the carpet—to investigate the yellow streak. I have come to hate the stench of urine. I don’t judge or malign the fact of urine—I hold no personal grudge. Urine is universal. But I loathe the smell. And entering the house today, acrid yellow vapors rushed up my nose. I hurried to mitigate the offensive odor by filling the carpet shampooer with soap and hot water and getting to work. The shampooer stands ready in its convenient corner for tomorrow’s use, for I will need it tomorrow, and the next day, etc. Noises, too, are triggering panicky heart beats and sweats. The squeals of school children running to the bus stop seem the screams of my mother in distress. The “thunk” of Mom’s magnetic shower door becomes the thud of my father falling. This morning’s Tchaikovsky bass drum booming might be, I wondered weirdly, Mom’s grief reaction to finding Dad dead in his recliner. Getting Dad situated in his new hospital bed, I felt zero confidence he could navigate the urinal in the night. I keep my bedroom door open at night now, listening for sounds I hope not to hear, lying awake in the quiet.

Courage at Twilight: A Heel and A Moron

Mom startled me with a sharp rap-rap on the door of my home office, where I sat focused on my laptop screen, lost in classic rock. She cried and squeaked out her Sunday afternoon plea for me to push her for a walk around the block. I detest being started, and reacted involuntarily harshly. “I don’t think it will rain,” she hoped. Thunderclouds thickened and lighting sheeted over the neighborhood—and the rain began to fall. With each passing car, I thought, They must think I’m such a moron for taking my parents in their wheelchairs in the rain. But we actually loved the gentle shower. Mom tilted her head back and spread her arms wide to the sky. All three of us wondered if I would be struck by lightning. In the moment, I didn’t care. Returning home, I saw that the porch lights were on, three hours before sundown. With such irritation, I have been snapping the porch lights off, for months. Why does she turn the lights on so early every day, I finally asked her. “I turn them on for you, to welcome you home from work.” Finally I saw the early-afternoon porch lights for what they were: a mother’s welcome home to her little boy who has been away all day. I such a heel, I thought. A moron and a heel. Before situating Dad back into his recliner, I studied the multicompartmentalized cushion he sits on, designed to avoid pressure sores. The cushion had flattened over the months. Mom watched me intently as I tried and failed to use the tire pump, the bike pump, and the ball pump, struggling to inflate the cushion. The stem closed with clockwise turn, but by the time I quickly closed the stem, the cushion had lost all my hard-blown air. I sat on a stool with the stem between my teeth, still blowing, and spinning the cushion around to close the stem. “Thanks for doing that, Roger. I have a pressure sore on my butt, and a full cushion should help.”

Courage at Twilight: Family Reunion

Dad’s brothers and sister decided to host a family reunion, the first in perhaps 20 years. I barely had energy to show up for the event. But I love my Baker-Formisano aunts and uncles: Bill, Louise (deceased), Howard, and Helene. I warmed to the occasion, happy to see my cousins and their families after so many years. One cousin I once knew well approached me and hesitated, “Now…you’re….” In fairness to him, I had a full head of hair the last time he saw me. When it came Dad’s turn to speak to the assembled hundred family members, I winced at the incoherent story-ramble that might emerge. Perhaps that was unfair of me, because he delivered a string of delightful stories about his direct ancestors, starting with Niels Bertelsen. Niels was a Danish fisherman who converted to our Church in the 1850s, a scant two decades after its founding in Palmyra, New York. The Bertelsens had no money to emigrate as a family, so Niels and ___ sent their children across the Atlantic Ocean, across the North American continent, one child at a time, without chaperone, as they could afford. Nicolena, only 10 years old, crossed the ocean without family, and worked as a maid in New York City for two years, without a family, until she had enough money to join a company of Church members walking the thousand miles west to Utah Territory. Needing to support herself in Richfield, a married Lena opened a store selling beautiful dresses she sewed. Her son Nelson became the engineer and foreman of the Prince silver mine in Pioche, Nevada. Nelson’s mining machinery manufactured steam, and he invented a clothes-washing system attached to the machinery, washing all the family’s laundry. His wife Natalia Brighamina, from Sweden, baked bread weekly, and fried sugar doughnuts from the extra dough for the mining town’s children. Natalia was Dad’s grandmother, and he knew her and loved her. She played a pump organ and sang the old cowboy songs with the family. Her doughnuts, her organ, and her lovingkindness made her popular and well-liked by the community. As a small child, Dad whispered to her one day that he was hungry and would like a slice of bread with jam. “Speak up, Sonny,” his father mocked, embarrassing the boy. “We can’t hear you, and we all want know what you have to say.” Natalia stood up her full 5-foot 2-inches and said sternly to her son, “I heard him perfectly well,” and led little Dad into the kitchen for his bread and jam.

Courage at Twilight: Block Party Four

Darrel and Mary Ann brought the half-page flier to the house, inviting us to “please come” to their annual block party. This would be my fourth since moving here. Why not roll the wheelchairs over? I thought. I could push Mom’s, and Dad could roll his own. Dad almost agreed to go, but an urgent and unpredictable bladder discouraged him and convinced him to stay home. But Mom rolled eagerly in front of me to the back-yard dinner party. I know her tastes, and served her a hot dog with ketchup, dobs of rotini salad and coleslaw, a triangle of watermelon, and a chocolate chip cookie. She gabbed happily with the neighbors, old and new, each so friendly. “Where does the name of Hughes come from,” she asked one neighbor, then launched into a discussion of her own ancestry. Still in my shirt sleeves and tie from work, the new neighbor asked me if I were just coming from work, or my formal business attire was “just how you roll.” I felt accepted either way. An evening breeze tempered the September heat as the sun set again over the Great Salt Lake, mirrored in the water, early enough to feel like fall. This is nice. I thought. I made Dad’s plate and set it in a mixing bowl: burger patty with melted Havarti, a fried egg, bacon slices, a tomato slice, and the house mayonnaise-ketchup-mustard sauce, with dog in mustard on the side. Mom carried the bowl on her lap as she rolled happily home. “Is that for me?” Dad enthused, accepting the mixing bowl and launching into the burger. The homemade chocolate chip cookies were to die for, and I brought home three for myself.

Courage at Twilight: Blocking Pucks

After dinner, I showed Dad the conference program from Utah League of Cities and Towns convention, an annual gathering of elected municipal mayors and city councils and their appointed senior staffs (e.g., me). I told him how much I enjoyed the keynote presenter, the goalkeeper from the 1980 U.S. Olympic gold-medal ice hockey team, which defeated the Soviet team for the first time ever—the “miracle” team—and who translated the principles of his athletic success to management. On the rink, he had blocked 63 puck shots with his body armor and stick, allowing only two goals. Dad perused the program and asked, “Did any of these classes have to do with your job?” What I heard him say was, You didn’t belong there. It was a feel-good waste. You should have been in your office working, not out hob-knobbing at some irrelevant conference. Perhaps that was not fair of me to mind read in this manner. But I have worked as the Tooele City Attorney for more than 30 years. I know my job. And I don’t need his approbation to go to this or that class or conference. I decided to answer his paternalistic question with my own humiliating fealty: “Of course, they have to do with my job, or I would not have gone to them” and by identifying the law-related sessions (which was all of them) and reminding him of the importance of making myself a valued member of a municipal team which includes six elected officials, all of whom rely on me, all of whom expect me to be the smartest person in the room, and all of whom can fire me. I felt annoyed with myself at having answered him at all, when what I really wanted to do was say Whatever.

Courage at Twilight: In the Mirror

Puzzling over the contents of the deep freeze, fridge, and pantry, I announced to Mom and Dad, “I think I’ll bake your favorite crispy butterfly shrimp tonight. Okay?” Mom nodded her smile. “Yes!” Dad exclaimed. “With rice!” I had thought to steam cabbage and slice cucumbers, I told him, and he called back, “Whatever.” What does “whatever” even mean? His “whatever” sounded to me like a passive-aggressive wishing for rice, which I would feel guilty for not cooking, and would, of course, now cook. But what did I care what “whatever” meant? I cooked his rice and steamed cabbage and soaked cucumber slices in salted vinegar. Dad met his plate with his standard sincerity, “What a beautiful-looking dinner, Roger!” When I arrived home from work at 7:00 p.m. that evening, he held a personal mirror in one hand and a tiny scissor in the other. As I cooked his rice, I heard him inform Mom, “I can’t see any more nose hairs in the mirror,” indicating he thought he was done. “Well, they’re there!” Mom called back gruffly, indicating she thought he was not. He guessed he would have to look again, he confessed meekly. I did not want to know about his nose hairs. Whatever.

Courage at Twilight: I Don’t Need You

Difficult conversations targeting personal inadequacies and vulnerabilities seem to lodge choking in my throat for days, or weeks, or years, and sometimes forever. But my distress pushed me into a chair to try. I began by telling Mom and Dad how my physical health has been in decline, with the nurses recording my blood pressure—four times—at 200/100, thinking, surely, there must be a mistake with the cuff. Google announced I was at risk of death, and ordered me to proceed immediately to the emergency room. And then there is the exhaustion, feeling too tired to sit upright in a chair, and curling up on the concrete floor of my office every day, behind my closed door, waking always to the timer I set for 20 minutes. Next, I recounted my worsening mental health, the depression, the mental fatigue, the hopelessness, feeling trapped and stuck, feeling the pressure every day of Mom’s and Dad’s conditions, of their very lives and deaths, waiting every moment for the next fall, cleaning up the messes in the kitchen and bathrooms, shampooing the carpets, the rusty weight of 100 things needing doing daily for their comfort and safety. The third anniversary of my moving in with my parents, on August 1, has just passed. The journey has been long and traumatic and exhausting, and I have felt desperate for a change. But I am caught in this in-between world, living for them instead of progressing in my own life. That change may be moving them to an assisted living facility and me finding a place to live, creating time and space to pursue my own dreams, to get married, to retire, to travel, to visit my children and cuddle their children. For this particular difficult conversation, it seems, I chose the wrong approach. They would hear nothing of it. “You do nothing for me,” Dad declared. I am doing just fine by myself. The CNAs come every morning to bathe me and dress me and feed me and settle me for the day in my recliner. Your mother applies the creams and powders at night for infection and fungus and pain. I brush my teeth and use the bathroom by myself. True. All true. “I don’t need you to do anything for me,” he said with iron will, becoming again the heavyweight fighter, the champion, pummeling every challenger. Feebly, I jabbed back with a dozen or two tasks I do for him regularly, and he left-hooked and upper-cut each one. Unfairly, perhaps, and desperately, I quoted Sarah, who told me before she died that Dad would have been in a nursing home two years ago if not for me. “Sarah was wrong!” he denounced. “I do not need to be in a nursing home, and I’m not going!” And in a rib-cracker he told me I had manufactured all these pressures in my own mind, that they were fake. “If you think you would be happier on your own, then move out.” But you will find yourself more alone than ever, he said. The only reason you’re alone here is that you retreat to your room. You could socialize with us if you wanted, but you don’t want to socialize with us. You run off to be alone in your room.

Courage at Twilight: Giving a Tug

“I want to go by the bushes and trees,” Dad insisted at the end of a wheelchair walk around the block. “Put on your list, for whenever you get around to it , to trim the junipers back from the sidewalk.” I was reluctant to do so, I said, worried I would cut off all the green and leave only the bare ugly inside sticks. “Do it anyway,” he said imperiously, admitting no discussion. And I bit out a stiff, “Yes, Sir.” Mom invited her doctor (and neighbor) over to see her needlepoints that adorn every wall. He politely wandered the house, exclaiming, “Oh my gosh!” at each frame, and she beamed. Quinn quizzed Dad from a paralegal coursebook. As 9:30 p.m. came, and Quinn asked Dad if he wanted to discuss another legal scenario, I bristled at the late hour and Dad’s flagging energy, but Dad answered “Absolutely!” and they kept at it, Dad’s legal mind as sharp as ever. I fled the house for a Saturday hike, a long hike, the longer away the better, and before the midpoint my phone dew-dropped with Mom’s text: Will you be home soon? I need you to take me on an errand. I responded, No, I will not be home soon. No, I will not be home, ever, I wanted to type. As I nursed my bottle of Gatorade after the hard hike, Dad randomly asked if I knew a particular song, and began croaking out “Sunny Side of the Street.” One of my favorite Frank Sinatra covers. Mom soon added her higher-pitched screech, and the melody flattened into a gravelly two-tone monotone. After the song, Dad struggled and shook to stand tall enough to push his walker toward the bathroom, dribbling along the way, muttering desperately, “Oh, God. Help me, Abba!” and cursing his routine “Damn!” as he worked to coordinate the walker, the door, the handrails, his pivot to sit down, and pushing down his sweat pants. “Rog, give my pants a tug,” he called on his journey back to his recliner. “I couldn’t pull them up by myself.” Yes, Sir. Oh, God. Help me, Abba.

Courage at Twilight: A Sort of Ending

At almost 89 years, Dad just keeps waking up every morning, day after day after day. His t-shirt garment tops are too tight around the neck and try to strangle him in his sleep, so he sleeps without a top now, or a bottom. Life is simpler that way. Mom pulls the shower door closed regularly at 8:00 AM with a bang which I have learned is not a body falling to the floor. This morning, I needed to escape the comfortable incarceration of home to seek beauty on nature’s trails. That seems to be my life’s aspirational pursuit: finding beauty. The twisted canyon where two glaciers once ground away at each other seemed unusually lush. On their steep meadows, cut gently by a meandering snowmelt stream, the wildflowers grew in excess of three feet tall, all of them: yellow-flowered strawberry, white columbine, lavender lupine, sticky geranium, both the pink and the white, firecracker penstemon, powdery blue bells, the unfortunately named beard tongue, larkspur, paintbrush, sweet pea, catnip, purple and yellow daisies, and blue flax. On this day’s journey to Desolation Lake, I climbed one slow step after another, steady. One just keeps going, on and on, up and up. Pretty middle-aged faces passed me, in both directions, and I said Hello to each, and each became the last in a long, knotted thread of lost opportunities to connect with another human being, for my lack of skill and courage. At the lake, feeling very tired, I stopped and sat on a log, for there is nothing wrong with stopping to rest on one’s journey. A small flock of hairy woodpeckers, almost a foot long each, graced me by landing in the ponderosa pines and quaking aspens, very near to me—one of them looked over at me, I am sure—and hammered at the trunks in rapid staccato. I wondered if the dasher’s one-hundredth-of-a-second stopwatch would still tick too slowly to measure the motions of these birds. They flew off, and I moved on to the mountain’s descent, not without growing pain from a swelling Achilles tendon. Never without pain on these trails, never without loss, and grief, all wrapped up in tenderness and love and the beauty of wildflowers and butterfly wings and birdsong and the burbling of water over rocks. Mr. Rogers and Kermit the Frog both have taught me that every ending is a new beginning, that every good-bye points to the next reunion. Forever. When does a story find its end? How does a writer know when to put down the pen? When, perhaps, it is springtime in the Rockies, and the swallowtails fly very close and bob their hello, and the stands of bluebells and columbines waive their petals against the canvas, and a bird I have not met sends her voice to echo through the trees with the loose embouchure air of a reedy flute.

Courage at Twilight: Holes

Prone in the dentist chair, Dad held up four fingers: “The last time I was here,” he misremembered, “the dentist pulled four teeth. Four!” The experience had been traumatic for him, and the pulling of two teeth may have indeed felt like four. Both yanked from the right side of his mouth, one was an old implant connected by a bridge to an artificial tooth, so the number of new holes felt like three. Dad winced as the hygienist cleaned the empty gums where a year ago had been teeth. “Is that sensitive?” she asked with unrhetorical kindness. “Uh-huh,” he managed. She explained that the empty pockets where the teeth had been can capture bits of food, and encouraged him to focus his water pick in those areas. The cleaning completed, and waiting for the cursory dentist check, Dad remembered how he had approached his mother repeatedly about the unbearable pain in his mouth, and how she finally took him to a dentist, and how his molars were full of decay, and how the dental solution of the mid-1950s was simply to pull the 14-year-old’s teeth: four of them. “I really felt violated,” he said sadly, looking far off into memory, a tinge of feal resentment still lingering these 75 years later. “Four teeth,” he lamented. Fourteen years after, “Doc” Nicholas constructed and implanted the bridge that would span the next 60 years until infection abscessed into the anchoring bone. My own mouth contains Doc’s excellent work from when I was 14 with decaying molars. Back at home, I invited Dad to coach me from his power wheelchair as I used his DeWalt trimmer to shape his three dozen bushes. “Do you want them flat-topped or rounded?” I asked, knowing already he would say “Rounded.” I paused frequently with the questions, Is this okay? and How’s that? A smile and a “perfect” were his consistent answers. The bushes had merged with spring growth, and I carefully reasserted the separations needed for the individual bushes to manifest, not unlike a row of clean but crooked teeth. Perfect. We both sat exhausted in the family room after our exertions. I commented again how glad I was he enjoyed the framed photo of Sarah surrounded by her nieces and nephews. “Yes,” he said, slipping into sadness. “I still feel some painful hole inside me that won’t be filled.” I feel that hole, too, Dad. He wrote to one grandson this week, “I still cannot cope with Sarah’s death, that she is gone. When I think about it, I feel overwhelmed with some dread feeling. I do not know what to call it, but ‘sadness’ is not enough.” He went on to write that he is by nature a happy man, blessed in many ways, and expressed his determined belief that we create our own happiness when we follow the principles of happiness, the greatest being love.

Courage at Twilight: Postcards

Steve wrote to Mom on a Banff postcard that they saw lakes and waterfalls and mountains, and elk, and a porcupine, and two bears. “A porcupine!” Dad laughed. “If you use its real name porcupine nobody knows you’re talking about a porcupine!” Mom and I looked askance at one another. “Um, Dad, could you clarify about porcupines?” I ventured. “You know,” he explained, “everybody knows what a porky-pine is, but nobody knows what a poor-KYOO-pine is.” I felt marginally better that his joke’s punchline made some sense. “Is today a holiday?” Dad asked, and I told him it was Juneteenth. “Explain to me the significance of Juneteenth,” he inquired sincerely, and I explained that Union armies had arrived in Texas on June 19, 1865, to find that the Black American slaves of Texas did not know that they had been emancipated, two-and-a-half years earlier, on January 1, 1863. They were the last African-American slaves to join the ranks of the newly free. This newest federal and Utah state holiday celebrates the end of slavery, Black manumission, and the continued struggle for racial and class equality in America. “I’m glad we have that holiday,” he said soberly. An hour later Dad asked me, “Is today a holiday?” and I sighed, discouraged. I also felt discouraged by the reality of taking Mom and Dad to the dentist on the holiday afternoon. I kicked irascibly against the brick wall of my duties. Interrogating myself about my anger, I realized I was not being petty or selfish; instead, I was afraid: afraid of the grueling car and wheelchair routines, afraid of repeating our near falls from the wedding day outing, afraid of so much of what is living life with ancient disabled parents. I have been sharing with Dad my impressions of Frederick Douglass, John Lewis, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Harriet Tubman, from their biographies. “So much has changed for Blacks, for the better,” Dad offered as I drove across the Salt Lake valley. “Much has changed,” I agreed, but expressed my discouragement about my country’s regressions on voting rights. One hundred years after the first Juneteenth, almost to the month, President Lyndon Baines Johnson maneuvered the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through Congress, riding the spiritual momentum of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the unconscionable police brutality at the foot of Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, and the shocking television images of Bull Connor’s squads turning fire hoses and furious dogs upon more than one thousand of Montgomery’s Black school children. Since its passage, politicians have fought against the Act’s protections, passing many hundreds of laws to restrict the Black vote. And after 50 years of leveling the voting field, the Act’s key provisions were ruled unconstitutional by the Roberts Court, overturning decades of Supreme Court precedent and Congressional support. “That is discouraging,” Dad agreed. We returned home by way of JCW’s for celebratory burgers, Mom and Dad so glad to have their teeth thoroughly cleaned, relieved to have no new cavities or infections, and thrilled to have Mom’s escaped crown glued back on.

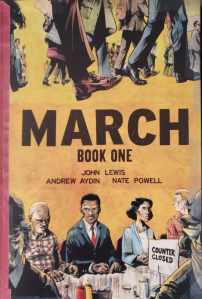

Pictured above: the cover of the late Congressman John Lewis’ award-winning graphic novel March, Book 1. The book (and its sequels) reawakened interest in the Civil Rights Movement among 21st-Century Black youth.

Courage at Twilight: Fiercely Red