Steve wrote to Mom on a Banff postcard that they saw lakes and waterfalls and mountains, and elk, and a porcupine, and two bears. “A porcupine!” Dad laughed. “If you use its real name porcupine nobody knows you’re talking about a porcupine!” Mom and I looked askance at one another. “Um, Dad, could you clarify about porcupines?” I ventured. “You know,” he explained, “everybody knows what a porky-pine is, but nobody knows what a poor-KYOO-pine is.” I felt marginally better that his joke’s punchline made some sense. “Is today a holiday?” Dad asked, and I told him it was Juneteenth. “Explain to me the significance of Juneteenth,” he inquired sincerely, and I explained that Union armies had arrived in Texas on June 19, 1865, to find that the Black American slaves of Texas did not know that they had been emancipated, two-and-a-half years earlier, on January 1, 1863. They were the last African-American slaves to join the ranks of the newly free. This newest federal and Utah state holiday celebrates the end of slavery, Black manumission, and the continued struggle for racial and class equality in America. “I’m glad we have that holiday,” he said soberly. An hour later Dad asked me, “Is today a holiday?” and I sighed, discouraged. I also felt discouraged by the reality of taking Mom and Dad to the dentist on the holiday afternoon. I kicked irascibly against the brick wall of my duties. Interrogating myself about my anger, I realized I was not being petty or selfish; instead, I was afraid: afraid of the grueling car and wheelchair routines, afraid of repeating our near falls from the wedding day outing, afraid of so much of what is living life with ancient disabled parents. I have been sharing with Dad my impressions of Frederick Douglass, John Lewis, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Harriet Tubman, from their biographies. “So much has changed for Blacks, for the better,” Dad offered as I drove across the Salt Lake valley. “Much has changed,” I agreed, but expressed my discouragement about my country’s regressions on voting rights. One hundred years after the first Juneteenth, almost to the month, President Lyndon Baines Johnson maneuvered the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through Congress, riding the spiritual momentum of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the unconscionable police brutality at the foot of Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, and the shocking television images of Bull Connor’s squads turning fire hoses and furious dogs upon more than one thousand of Montgomery’s Black school children. Since its passage, politicians have fought against the Act’s protections, passing many hundreds of laws to restrict the Black vote. And after 50 years of leveling the voting field, the Act’s key provisions were ruled unconstitutional by the Roberts Court, overturning decades of Supreme Court precedent and Congressional support. “That is discouraging,” Dad agreed. We returned home by way of JCW’s for celebratory burgers, Mom and Dad so glad to have their teeth thoroughly cleaned, relieved to have no new cavities or infections, and thrilled to have Mom’s escaped crown glued back on.

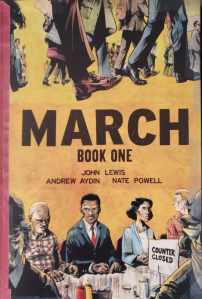

Pictured above: the cover of the late Congressman John Lewis’ award-winning graphic novel March, Book 1. The book (and its sequels) reawakened interest in the Civil Rights Movement among 21st-Century Black youth.