Over the course of three days, three of the chandelier’s 16 candle-flame bulbs burned out. I suspected Mom would notice the blackened bulbs immediately, and my suspicion was confirmed by the immediate appearance of a package of new bulbs on the countertop wanting me immediately to install them. At a height of 12 feet, replacing bad bulbs required a tall step ladder, hanging in the garage, carried with care for the cars and wall corners. Not my favorite job. But I would get to it—when I felt like it. My son John brought his little family over the next day for an Easter egg hunt. Three-year-old Henry helped his dad hide the eggs, then raced to find them all, then begged to hide them again, to which, of course, we acceded. When John walked in the front door, laden with children and plastic eggs, Mom immediately called out to him with a guilty giggle, “John!! Do you feel like climbing a ladder?” I all but shouted at her that I will get to it, Mom, when I’m ready! You don’t need to ask anyone else! Two days later, my brother was visiting from North Carolina. Before Mom could ask him to change out the bulbs, I grabbed the ladder, dragged it without a ding down the hallway, and climbed with an armful of fresh bulbs. The chandelier’s heat on my too-near head surprised me. I replaced the bulbs, then replaced the ladder, then went to my room to change from my jacket and tie. I heard Steven cheerfully ask Mom, as he approached from his own room, “Should I change the bulbs now, Mom?” Having desired an immediately replacement of the blackened bulbs, she had had to wait days for her slow firstborn son, who confessedly moved slower for her hurry. With new bulbs, the house has settled back into its calm fully-lit brilliance.

Tag Archives: Dementia

The Dementia Dossier: Locked Out

My briefcase and lunch bag and shopping bags hung from my wrists and hands, and I strained an arm awkwardly up to turn the handle of the door from the garage where I had parked to the house. Ugh, I thought when I turned the nob and the door remained closed, she locked me out. Again. Down went all my bags so I could pull my keys out of my pocket and let myself in. The big electric garage doors are shut all day, so no threat exists of a stranger entering the house through that door. Only I come through that door, precisely once a day after work. I have asked Mom not to lock me out, and she apologizes, with no awareness of having locked the door. I deduced that when she habitually turns on the outside garage lights (three hours before dusk) on a trip to the bathroom, she habitually turns the dead bolt to lock. Instead of complaining, I should just assume the door is locked and have my key ready.

The Dementia Dossier: Four-Leaf Clovers

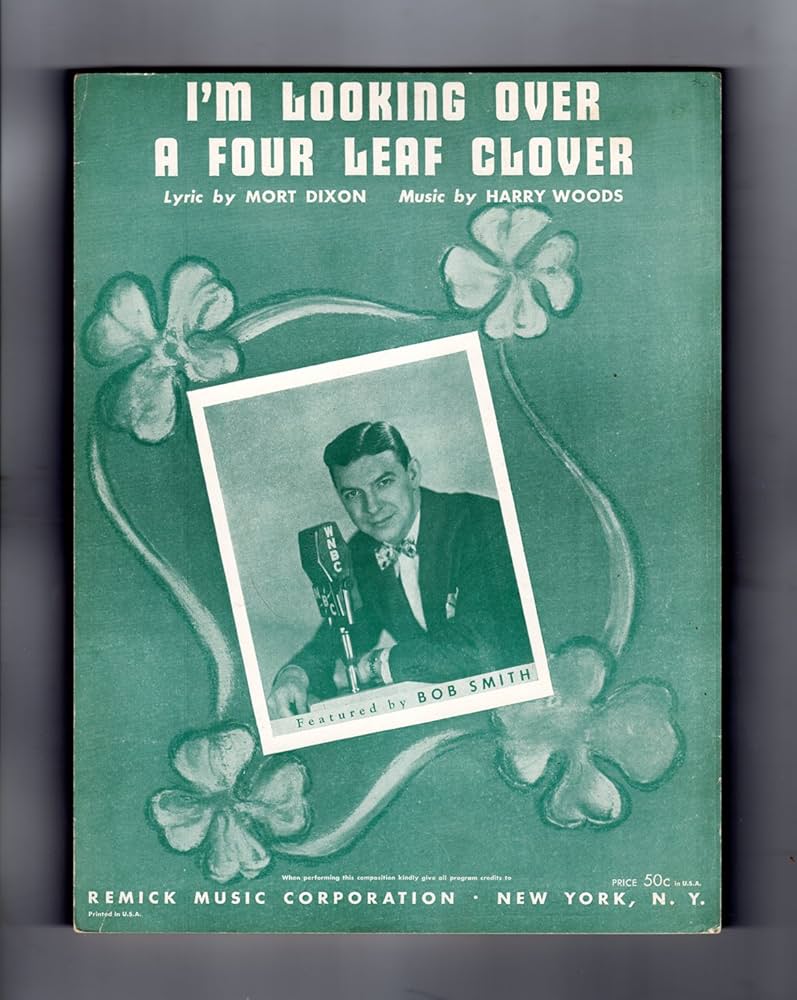

My date and I sat on the sofa with a sibling and a nephew wondering how to spend the evening, whether to watch a movie or play a game or just talk. “We could sing songs!” Mom piped up. “Do you know ‘I’m Looking Over a Four-leaf Clover’?” And she launched into the 1927 song with the unsteady tin of old voice:

I’m looking over a four-leaf clover that I overlooked before.

One leaf is sunshine the other is rain. Third is the roses that grow in the lane.

No need explaining the one remaining is somebody I adore.

I’m looking over a four-leaf clover that I overlooked before.

At first, I felt mortified, but my date knows and loves my mother and didn’t mind the cute oddity. I even found myself joining in, since I, too, know the old song. Still, I felt relieved when the verse ended. We quickly moved to casting family photos to the TV. When I voiced a frustration that I couldn’t manipulate the casted photos from my “Samsung,” Mom brightened: “You want to sing more songs?”

The Dementia Dossier: A Mystery

Tidy, but not fanatical. I think that describes me: Tidy. Everything (mostly) has its ordained and proper place. My dress shirts all hang on wooden hangars in roughly color order. My 50 years of black-binder journals line my shelves in date order. My lap pillow sits in my recliner waiting to prop up my book when I sit to read. My bed is made, my vases and bowls decorate my dresser, and the floors are absent of random items. On occasion, I have noticed (or thought I noticed) certain items not in their usual places. A decorative bowl has moved two inches to the left. My bedroom blinds have been opened. My lap pillow is on the floor. (Yes, I am sure of it: things have definitely moved.) Most concerning, a recent journal volume has not been fully replaced in its spot. Sarah warned me once that Mom knew things she shouldn’t know and couldn’t unless she had been reading my journal. Knowing that Mom is looking out my window or touching my decorations or sitting in my chair doesn’t trouble me greatly—they are not real violations, just strange wanderings. But her reading my journals I cannot abide. I resolved upon a strategy which would communicate without accusing, and placed a warning sign on the last journal binder moved: Please Do Not Read My Journals. Things have moved around less since, and the journals not at all.

The Dementia Dossier: Trust Me

Twelve of our three dozen padded folding chairs reside in a neighbor’s closet to facilitate church choir practice at their house. “There are 12,” Kevin pronounced, all labeled Baker, as we loaded them into the back of Dad’s faithful Suburban. We needed all our chairs for the Friday mission reunion, and indeed used them all. After the reunion, I stacked the 12 choir chairs against the wall, leaving out a 13th for me to use with the TV tray during dinner. On Sunday I carried the 12 chairs four at a time to the car, leaving the 13th behind. “But there are 13,” she said anxiously. No, there are 12. “No! There are 13!” she wailed in near panic. I reassured her I had brought 12 chairs from the neighbor’s house—“Trust me”—and that 13th was to stay behind for me to use. The same evening, I piled the bulk pickup refuse at the curb where I usually place the garbage and recycling cans, moving them instead to the mailbox side of the house, but a good distance from the mailbox so the mailman could easily pull up his truck. Mom instructed me to make sure I didn’t put the cans in front of the mailbox, “because the mailman won’t come.” She seemed really worried. “Mom, trust me,” I insisted, “I know how to do this right.” I promised to leave plenty of room for the mail truck. She remained dubious on both accounts.

(Image by Clker-Free-Vector-Images from Pixabay.)

The Dementia Dossier: Throw It Out

Dad’s personal papers filled filing cabinets and drawers and shelves and box upon box: study notes and drafts of his book Process of Atonement; correspondence; mission papers; journals and memoirs; travel brochures for family vacations; investment and bank statements; tax returns; and much more. As I emptied hanging file folders to shred no-longer-needed papers, I removed the clear plastic label tags and dropped them in an empty desk drawer for later use. That later use came several days later as I began to create new files for life insurance papers, home and auto insurance papers, pension and health insurance papers, family history records, and others. But when I pulled open the drawer with the clear tags, I found the drawer empty. “Mom,” I called out. “Where are all the file folder tags?” She looked confused and said nothing. I retrieved a tag from an active file drawer, and asked her where all the tags I had saved might be, if she knew. Her confusion turned to embarrassment as she confessed to not knowing what they were so she threw them away. Why would you do that? I thought. “Please don’t throw things away just because you don’t know what they are. Please ask me first.” She whispered an Okay. Scraping the dinner dishes into the kitchen trash bin later that day, I found several new clean vacuum filters in the trash. “Mom. Why are these new vacuum filters in the garbage can, if you know?” She had really wanted to clean out the hall closet, she said, [and I hadn’t done it fast enough for her compulsion,] and she didn’t know what they were, she said, so she threw them away, she said. I told her what they were and put them back in the now-empty closet.

(Image by gugacurado from Pixabay.)

The Dementia Dossier: Listening

Two men from the church came to visit Mom, one a teenager and one recently retired. In addition to the box of Crumbl cookies, they brought their love and interest and supportive smiles. And Mom gave them each her big bouncy full-bodied hugs, and they laughed, even as I cringed. I had set holding chairs out for them, in front of Mom and her recliner, and I listened from the kitchen, wanting Mom to have their full attention. Stewart and Brendan had come just a few days before Dad passed away, and here they came again to minister to Mom with words of comfort and love (and with cookies). The subject of death has been tender and frequently on our minds. Mom asked about Stewart’s son who died, long ago, of meningitis at age 10, and Stewart was coming to the crux of the terrible story, about how even in death he had felt profound love and peace and a divine Presence. As Stewart stopped for a breath, Mom looked at Brendan and asked him about his favorite subject in school. The sudden change of subject, at such a dramatic and touching moment, left me feeling jarred. What mental mechanism of Mom’s caused that? I wondered. I know she loves and cares about people. I wondered if she even heard the story, or felt the emotion in it, or if she just couldn’t focus on one subject or story line for long, no matter how poignant. Steward took the jolt in stride, understanding and not judging, loving her notwithstanding. Still, as I escorted the men out through the front door, I made a point of thanking Stewart for sharing his story, and of standing with him for a moment in his resurgent pain.

(Photo from Pinterest, used under Fair Use.)

The Dementia Dossier: Just Lazy

Plantation blinds allow abundant natural light in Mom’s living area. But after dark she feels exposed, and turns the wood slats to the shut position. I’m sure the only voyeurs are mule deer, but I understand and agree with her desire for privacy, and her caution. When I brought Mom’s dinner to her in her recliner one night, she said, “Close the blinds behind me, will you, dear?” She has a wooden yard stick for precisely the purpose of pushing the slats closed, but using it requires her to stand up from her position of supine comfort. “Well, that’s your job, Mom,” I reacted, perhaps a little too abruptly. I have encouraged her to keep up her strength and independence by doing as much for herself as she can. “Oh, alright, dear,” she responded with a tinge of chagrin. “I’m just being lazy.” All the more reason for me not to have immediately acquiesced. The next day, when I came home from work and sat down, she said, “Get the mail for me, will you, dear?” The mailman hadn’t come when she went out for the New York Times. I reminded her that her walk to the mailbox is pretty much her only exercise, and I was sure she could get the mail, there being no snow or ice or rain. “Oh, alright, dear,” again the subtle rebuke. “I’m just being lazy.” And on a Friday morning that I worked from home, she called to me in the kitchen, “Get the newspaper for me, will you, dear?” I stared hard at her and did not speak. “Normally I would get it, but you’re here,” she explained. Precisely, I thought piously through my stare: This is something you can do. “Oh, alright, dear. Never mind. I’ll get it. I’m just being lazy.” I am not about to be put to work in compensation for another’s laziness. But I suspect the issue isn’t so much laziness as it is the comfort of being helped and cared for and even pampered when one is 85 and always tired and life is lonely and every chore seems to take so much energy.

The Dementia Dossier: Smacking

Mom has never been one to chew with her mouth open, and she certainly taught me as a little boy the same principle of social and eating etiquette. But she must love, or be absolutely oblivious to, the crunching smacking sounds of certain foods. Her routine breakfast includes a bowl of dry honey nut Cheerios with milk on the side in a glass. With each fingers-full of Cheerios, the first five quick delighted chews are with the lips parted and the full crunching reverberating through the downstairs. At least that how it seems to me. After breakfast comes the Mentos Pure Fresh peppermint gum, chewed with wet delighted smacks. Over the course of months, I have spent hours composing messages of gentle and not-so-gentle confrontation. Could you please chew with your mouth closed?! An obviously rude question destined for failure and offense. Your chewing is pretty loud. Still too direct. The right message and the right delivery are important to an old person whose dementia takes the form of anxiety and sweetness and deference and wanting always to be good. The casual candor I might otherwise employ could really hurt my mother’s fragile feelings. Finally, I landed upon the perfectly balanced approach, I thought, with the benign observation, I can tell you’re really enjoying your gum. She looked slightly embarrassed, but not ashamed or belittled, and responded that she was, she guessed, and that she was chewing a little loud, she guessed, and she would try to remember not to smack. I’m sure she had not noticed her crunching and smacking before, other than within her own skull, because she hasn’t been able to hear life’s smaller sounds. With her new hearing aids, she likely will be more aware.

The Dementia Dossier: Egg Salad

Mom has refused to wear the hearing aids she bought three years ago, because the piece that sits behind the ear conflicts with her glasses frame. My siblings and I have begged and remonstrated with her—we have tired of shouting, and of the 5:30 news driving us from the downstairs—but she just turns red in the face and won’t talk. She was open, however, to the idea of new and better hearing aids. Surprisingly, Dad’s medical insurance paid a nice benefit, and she ordered hearing aids that sit entirely within the ear. “Look at the pretty clouds,” she said. “Look at all the airplanes! I can’t believe all the airplanes.” We finished our errands early, and she insisted on going to the audiologist office an hour early. “We can sit and wait.” And I insisted I was too hungry and we had plenty of time for lunch before her appointment. (I wasn’t going to sit and wait for an hour.) She relented and tried to suppress her anxiety. I asked her what sounded good for lunch. “An egg salad sandwich,” she replied. “I like egg salad.” I raised my eyebrows at her, and wanted to remark, You’ve never asked for egg salad before! Where do you think we’re going to find egg salad around here? I was thinking of a hamburger. We opted for a little Vietnamese place next to the audiologist, and wouldn’t you know it, they served an egg sandwich. Mom loved it.

The Dementia Dossier: Lights Blazing

Arriving downstairs at 9:00 a.m., Mom turns on the front foyer chandelier then hand surfs the walls on her way to her chair, switching on every ceiling light and desk lamp as she goes. It is as if she finds herself in a long dark hallway, flipping on lights a section at a time as she goes so that she can find her way to the next section and eventually her destination. She seems oblivious to the unseen lights left on behind her—they have served their purpose and now simply to not exist in her consciousness. Eventually her surfing surface ends and she settles heavily in her rocking recliner, encompassed by five burning desk lamps and 25 blazing recessed spot lights. The brightness screams at me but seems to soothe her. I much prefer the softness of natural window light, which we have in abundance, and enjoy shadow over direct beam. On the days I am home, I routinely turn each light off as I follow her throughout the house (except those light she needs in her immediate vicinity). Watching television becomes painful to my tired eyes as the room’s intense glare hits me from many directions and reflects off the dim screen. Some days I just cannot endure the light, and inform Mom I need to turn some lights off and dim others down. She relents. I have urged her to turn the lights off in the unoccupied rooms, to save on the pricey power bill, and to practice a bit of conservation. (We are recyclers, after all.) But it is her house, and she pays the power bill. One hallway lamp in particular I turn off as I pass by and she turns on as she passes by, and back and forth. I quickly tire of the power struggle and let her win the game. The light, she says, helps her see her needlepoint work. And the brightness seems to help her feel cheery and less alone. The brightness provides some physical compensation for the emotional isolation which is her new daily routine. Just shy of 10:00 p.m., she reverses her routine, turning nobs and flipping off switches as she makes her nighttime circuit toward the chair lift and the upstairs and sleeping in the dark, buried head to toe under her blankets.

The Dementia Dossier: Running and Jumping

No matter how miserable Dad felt in life, his answer to the question How are you? was always “Marvelously well, thank you.” Always. He might change his tone, moving from enthusiastic to tired to silly. But he was always “marvelously well.” Now it is Mom’s turn to answer all the retired older ladies at church when they put their arm around her shoulder and squeeze and ask How are you? She begins with a simple, “I’m fine.” But then she explains how she is not sad, that she is happy, because when she pictures her husband of 62 years in the afterlife, “I can see him running and jumping!” she says. Always running and jumping, and not alone either, but with my ebullient sister Sarah, and with his beloved sister Louise, and with his tender grandmother Natalia. They are all running and jumping. In the afterlife, apparently, people do a lot of running and jumping and who knows what else. And who am I to say that all the good souls in the afterlife aren’t running and jumping and rolling down green grassy hills? It is possible that Mom is simply willing herself to be cheerful and to think hopeful happy thoughts. Maybe Mom can’t tolerate the sadness and loneliness and is casting about for some glimmer to grasp. But perhaps she really believes it, that her husband is no longer old and sick and paralyzed, that her sweetheart is running and jumping his way to heaven, a now young and vibrant and carefree soul (though after 3½ years of caring for my old and sick and paralyzed father, I have a hard time envisioning his frolicking). But why can’t a frolicking afterlife be true? And why not believe it even if she can’t yet fully know? The very thought of her Nelson running and jumping uninhibited in heaven makes her happy, and what’s wrong with that?

The Dementia Dossier: The Calendar

Mom’s weekly hand-drawn poster-sized calendar is taped to the pantry door. I have learned to take quick initiative each Sunday evening to write my commitments on her calendar in order to avoid her gentle badgering to write my commitments on her calendar. She is smart to keep this calendar, because my explanations of events and dates and times quickly confuse and overwhelm her. As I wrote on this week’s calendar, she called from her recliner, “What did you put on the calendar?” I wanted to answer, What’s the point of me writing on the calendar if you’re just going to ask me what’s on the calendar? Why don’t you come and take a look for yourself at your calendar? She persists: “What did you write in green?” I opened the pantry door to show her, but she cannot read her poster from that far away. I sighed. “Tomorrow. 7:00 p.m. Planning Commission meeting.” That’s tomorrow? Wednesday? “Yes, Mom.” And the next night is the police department awards banquet, so I’ll be home late two days in a row. That one is written in fuchsia. I am slow to understand that her mundane uneventful daily routine means everything to her sense of stability and calm. Disruptions in daily the routine destabilize and frighten her. Add to this her loneliness. “I’m sad you’ll be gone,” she laments. “I will miss you.” And this time I actually do verbalize to her how inadequate a roommate I am for her, and how sometimes she becomes so clingy that I want to pull away. “I’m sorry, dear,” she whispers, defeated. Not only have I disrupted her routine with my green and pink events, but I have made her feel small and ashamed in her loneliness. She needs a better roommate.

The Dementia Dossier: Toss It

Mom and I remain proud co-recyclers, filling our kitchen recycling bin with cans and bottles and newspapers, and emptying the bin into the two giant green street cans sitting in the garage. Stepping down the two stairs into the garage is getting harder for Mom, even with the railing and grab bar. Instead of carrying a 12-pack Coke Zero box to the green cans, or a shoe box, or a cereal box (which don’t fit well in the kitchen bin), she merely throws the box toward the green cans, where the boxes sit on the garage floor waiting for someone—I can’t imagine who—to pick up. “Mom,” I remonstrated, “just put the box on the kitchen counter, and I’ll take it out. Don’t just toss it into the garage.” She apologized sheepishly, explaining that she just “got lazy.” I do acknowledge the sheer carefree liberation of tossing a box toward the can, released from the effort and duty of depositing the box in the can, and the moral certainly that someone will place the box in its proper place for street curb pickup and saving the rainforest.

Image by Clker-Free-Vector-Images from Pixabay

The Dementia Dossier: Introduction

Many of you followed Courage at Twilight as I recounted my experience living with dying parents. With this page, I am launching a new exploration. As my father’s mental abilities diminished, I naturally attributed the loss to senility, or more broadly and accurately, to dementia. He read for hours and hours a day until the final week, and he still comprehended and remembered more than I do when I read the same books. But his ability to comprehend, synthesize, apply, and remember the information began to suffer. The decline was mostly masked by his great intellect, but gradually became more noticeable. Where nine years ago he easily followed Word’s “accept” and “reject” functions while reviewing my suggested edits to his book Process of Atonement, in his last year he could not manage the power button, mute button, or any other button on the television remote. Alone with Mom now, I am observing on a daily basis her decline in mental function, short-term and long-term memory, and the ability to process new information and work through new problems. And I am pondering the spectrum of mental normalcy. I am well-known at work for remembering the details of 30-year-old incidents, but I notice my own mid-term memory fading, like forgetting that the City Council increased its golf course fees six months ago (I wrote the fee resolution). I am wondering: where does sanity end and senility begin? But that is the wrong question, presupposing that senility is the loss of sanity. It isn’t. Senility is the loss of memory. And don’t we all experience memory loss for once-remembered people, places, dates, and occasions? So, by becoming more forgetful, am I, myself, drifting into dementia? Where does dementia begin? On what date is my memory and cognitive function loss sufficient to say, “That’s when my dementia began”? I doubt such a date can be determined. But episodes characterizing dementia can be humorous, sad, or maddening (etc.), or all combined. In these posts I will record my mother’s little oddities, pointing together toward dementia and decline. I mean no disrespect in finding an aspect of humor in her decline. But humor often derives from the little human oddities of life, whether happy or sad. I am merely observing, and trying to make sense, again, of the ending of life. Each post here will be much shorter than this one—I promise—and will relate a small vignette illustrating the nature of inevitable human decline. I love and respect my mother—and she also drives me batty! Hopefully these entries will make you smile at, and ponder on, those we love whose earthly lives are winding down. I look forward to continuing my journey through life with you.

Courage at Twilight: I Haven’t Lost My Mind

Dad asked me to make an entry in his check registry, in which he keeps a scrawled and unnumbered untallied record of his checks. And that is where I discovered the $500 check made out to his dear hospice nurse. The image of the entry bounced erratically around my brain for hours, seeking but finding no possibility of legitimacy. I asked Mom and Dad if I could discuss something with them (“Certainly!”), explained about finding the registry entry, and asked what they could tell me anything about it. Dad offhanded the check as a simple Christmas gift, and turned back to his book. I pressed him about why this gift in this amount to this person. “I just thought she needed it,” he demurred, not looking up. I pressed further: but what did she say that led you to believe she needed money? He mumbled something about hard times and her husband being out of work, with Christmas coming. I launched, carefully, into a lecture about his days of monetary magnanimity being over, that his bank balance was low and diminishing, that giving his money away sabotaged my ability to take care of him, that my fiduciary duty to him required me to raise the subject of financial irregularities with him, and that, besides all these, his hospice nurse playing on his sympathies and accepting a gift violated hospice company policies, Medicare hospice licensure rules, and nursing ethics. What’s more, for a person in a position of trust and confidence (like a hospice nurse) with a vulnerable adult (like him) to obtain that vulnerable adult’s funds (like a $500 check), constitutes the crime of exploitation of a vulnerable adult. But I asked her if there were any rules that prevented her from accepting a gift, and she said no. Just a week earlier, Jeanette had warned Dad about another exploitative person who might ask him for money, and he had retorted that he could “recognize a con.” And yet here he had been conned. “I haven’t lost my mind,” he insisted to me, but he could see now he had been played, and he felt embarrassed. “I won’t do that again,” he promised. He looked to Mom, “We won’t do that again.” Lying in bed pondering the bizarre situation, I realized I possessed a new power, namely, the power to get the nurse fired: a power I did not want. We liked this nurse; we trusted her; she is a nice woman and a good nurse; and I did not relish reporting her and causing her pain. And that is part of the con. My sympathies were being played, too. So, I used the power I had been given: I called my contact at the hospice company and reported the occurrence of the gift. The same afternoon the company director called to tell me the gift had been investigated and confirmed, the nurse had been fired, the nurse would be referred to the Board of Nursing, and the $500 would be reimbursed. Thank you so much for calling. Sudden and severe, but not surprising. I fought to not feel responsible for the devastation just wrought in the life of the nurse and her family, due to my report, urging my brain to believe the truth that these were direct and terrible consequences of her actions, not mine. But I will not tell Dad that I reported the nurse and that she was fired, because his brain would lose the battle, and he would berate himself for giving the forbidden gift and destroying the gifted.

(Pictured: brick wall, with ivy, surrounding my daughter’s Chicago apartment back patio.)

Courage at Twilight: Do I?

“Close these blinds, will you?” Mom asked. Her habit has always been to stand, lean over her recliner, and push the slats closed with an old wooden yardstick. But now she waits for me to stand up from the couch or to enter the room, and asks me to do little things she no longer feels like doing. “Bring your Dad’s medicine, will you?” “Put your Dad’s checkbook in his office, will you?” My opinion is that I should not being doing for her things she is perfectly capable of doing for herself. Do I draw that boundary and risk hurting her feelings? No, I guess not, at least not tonight. Dad takes his turn, too: “Lucille, would you get my checkbook from my office?” I interpret “Lucille” as meaning “Lucille, Roger, anyone?” It is true that Dad obtaining the checkbook (or anything else) for himself is nearly impossible. “Your hair is beautiful,” Mom called to me after I delivered the checkbook to Dad. “That’s not possible, Mom,” I hissed. “I don’t have any hair.” She guffawed, “Yes, you do! And anyway, it’s the shape of your head that’s beautiful. I just love the shape of your head.” She cannot see my eyes rolling inside that beautiful hairless head, or my jaw muscles working in my face, or the energy it takes for me not to growl and bark. More and more I’m her perfect first-begotten bald baby boy in some weird Benjamin Button skit. On the counter lay a bag of moldy bread, which I threw into the kitchen garbage can. Throwing something else away later in the evening, I noticed the moldy loaf but not the plastic bag. Mom had salvaged the bread bag to recycle at Smith’s grocery with the blue newspaper bags and the brown shopping sacs and packing bubble-wrap and various other bits of bag plastic. Another day I discarded several mold farms growing on the forgotten cheese inside quart-size baggies hiding at the bottom of the cheese bin. And again I later found the molding cheese swimming bagless in the garbage can. Do I tell her how insulting it feels to have an old lady following after me and digging in my garbage, implying I should not have thrown this and that away, that I ought to be a more diligent recycler, that I should do things differently? Do I tell her Smith’s grocery does not want our moldy bread and cheese bags, our greasy leftover pizza zip-locks, our frozen vegetable bags? Do I point out how many gallons of heated treated water she uses to wash the bags out with dish detergent, the cost of the water far outweighing the damage of a sandwich baggie in the city dump? Do I tell her how annoying it is having all these wet washed baggies doing their damn best to dry scattered on the kitchen counters? Do I tell her the moldy cheese bag was in the garbage because I wanted it in the garbage, not because I’m lazy or apathetic or belligerent? I guess not. It should be easy for me to swallow that much pride, to let an old lady have her little quirks, for Mom to be cheered at the thought of helping to rescue the planet from plastic. I have drawn the line, however, at the gallon-size baggies that held raw chicken and raw fish and raw beef. “Mom. It’s just not possible to sanitize them,” I insisted. “Smith’s doesn’t want our raw-meat bags. Nobody wants them. And we might kill some innocent store clerk with salmonella-infested bags.” She reluctantly agreed to leave the raw meat bags where they belong, in the trash can, her feelings mostly intact.

Courage at Twilight: Lithium-ion

As I walked through the front door after work, Mom approached me with a written list of five things she needed help with. 1a) Dad’s printer would not work. She was right. I unplugged it and re-plugged it in, and it worked, but she had clicked the “Print” icon so many times that the resulting print jobs drained the ink dry. 1b) Replace the ink in Dad’s printer. 2) Dad’s gabapentin was about to run out, with no refills, so would I call the prescribing doctor to renew the prescription. I texted the hospice nurse, who had the medicine delivered to the house. 3) Dad’s glucometer stopped working, so would I go to Walgreens or somewhere and buy him another one—suddenly, after years of not testing his blood glucose levels, he wants to start testing his blood glucose levels, at age 88. I plugged the glucometer into my computer to recharge the battery as I wrote, and announced heroically that we would not need to buy a new one. “It has rechargeable batteries! Isn’t that amazing?” 4) Review the list of distributees for Sarah’s tribute book, which at 52 pages, including 12 color pages, would cost $12.25 a book to copy and bind. We cut the list of essential persons “who would still want to have the book in 50 years” (I suggested to him that no one would still want the book, or perhaps even be alive, in 50 years) from 60 copies to 40 copies, with the reassurance we could print more, if needed. 5) Write on the calendar the coming weekend’s activities. As Mom confronted me with the list, I asked a bit testily if I could pee first, because I had drunk too much passion-fruit-flavored ice water before leaving the office, and peeing was my first priority. Relieved, I set about the tasks, still in my hat and tie. Mom invited me to look in Dad’s office at how she had rearranged Dad’s power tool batteries and their chargers. Dad had kept her awake the night before repeating suddenly anxious expressions about the lithium-ion batteries shelved in his office closet—shelved by me, already responding to his anxieties about the batteries touching each other or their chargers and starting a 1200-degree F fire that would burn the house down, shelved by me alternating the chargers and the batteries, nothing touching anything else, with the tools far away in the garage. But he had forgotten, and had begun to panic again about lithium-ion infernos, and after midnight had sent Mom downstairs in her nightgown to redistribute the chargers and batteries more safely, so there was no chance they would touch. My completed or in motion, I examine with some confusion the closet shelf, now bare of batteries, and looked toward Dad’s L-shaped desks to see the chargers and batteries spaced there at distances of three feet each from the other. “Looks great, Mom. They’re certainly not touching each other. Nothing to worry about.”

Courage at Twilight: Cousin Party

Jeanette has come to visit. She came to lighten my load. She came to visit and to love and to talk with her beloved ancient parents. She came to lift and be lifted. Before she came, she organized a cousins party. “Come on Friday March 15 for pizza and brownies and lots and lots of games!” And they came: the autistic, the trans, the straight, the atheist and the priest, the gluten-free and the vegan and the red-meaters, the married and the single and the living-together—they all came, and demolished five extra-large Costco pizzas and devoured an enormous platter of raw vegetables and cleaned off three heaping plates of frosted brownies, and they told stories and played a game matching clever memes with ridiculous photos and laughed and laughed and laughed, red-faced and crying and together, a group of cousins with several things in common, like the presence of their aunt Jeanette, and the absence of their aunt Sarah, and their love for one another. One hermit-like cousin commented for only me to hear, “It’s so nice to be with people I actually like.” Jeanette’s energy was electrically ebullient and conductively contagious, at the center of the circle, catalyzing their inertia into uproarious fun. As the older uncle, I stood back and observed and rejoiced quietly in the transpiring of this knitting together of this grief-split generation. I felt keenly the sting-throb of Sarah’s violent departure. I saw no defect in the power of Jeanette’s presence, but merely the soft hole of Sarah’s absence. The gathering, happy and healthy and hilarious, nonetheless occupied the crystalline comet-tail haze of Sarah’s gone-ness. Dad motored into the room to bask in his posterity’s energy and mirth, but could not hear or understand the pop-culture drollery, and retreated to his recliner to rest and create his own quiet humor with Rumple of the Bailey and the Reign of Terror. I followed, to help his rise and pivot and point and fall, hearing loud echoes of hilarity from across the house. I felt sad for him, and I think he felt sad and lonely and resigned, but family is to him life’s great mandate, and I knew he felt mostly joy at the loving laughter of twenty cousins. Mom accompanied Jeanette to pick up the pizzas, giving directions as she had done (without need) a hundred times, but this time Mom could not remember how to get there, and led Jeanette the wrong way, and the Costco was no longer in its tried and true location, and Jeanette showed her the map, and Mom looked up and cried because she could remember no longer that which she always has known, and she knew she was old and she knew she was losing her faculties, and there was nothing she could do about it. We did find Sarah’s grave, though, and left in a crease of winter grass a brilliant bejeweled owlet with a poem inside, declaring “Do not look for me here. I am not dead.” Yes, actually she is. But her essence, indeed, is not there buried under nine feet of dirt, but in my heart and my hope and my faith, and I will believe—tell me, why shouldn’t I?—that she sees and hears and cares and will welcome me that day when my turn comes.

Courage at Twilight: The Bad Guy

On his way to help me peel potatoes for our dinner, Dad crashed his tank of a power wheelchair into his walker and snapped a walker leg. First came subdued cursing. Then came open self-deprecating laughter. “I crashed into my walker!” he grumble-chuckled, then began peeling. With only three people, we needed only five small potatoes. Back in his recliner for a dinner of Costco meatballs, mashed potatoes, and steamed broccoli, he pointed to the framed 8×10 of Sarah surrounded by her nieces and nephews, his grandchildren. “I love this photo, Rog,” he explained. “I find it quite comforting.” I felt relieved, since I had given him the photo, and I felt a glimmer of enlightenment about his turning the portrait of Sarah and him face down on the table: perhaps he simply does not like looking at his 88-year-old self; or, just as likely, perhaps he does not like seeing Sarah with only himself, being reminded of the “giant hole” he still feels and likely will always feel. Sarah stays with me, at least, in the sense of having her portrait on my desks at work and at home. Still, the family feels smaller to me. We were six sibling and now we are five. I had four sisters and now I have three. We were two Brazilian-born babies and now we are one. Sarah is simply irreplaceable. But I can say the same about my four living siblings: each is unique and remarkable in their own ways. Munching on meatballs, we watched the tenth episode in an animated science-fiction series rated TV-Y7. “Is he the bad guy?” Dad asked, and I said simply, “Yep,” but continued soto voce: and he’s the same bad guy we’ve seen in every episode. As the 24-minute episode ended, Mom queried, “Explain to me what happened?” so I elucidated the plot and character basics. After understanding the show, they asked to see another episode. “Is he the bad guy?” “What happened?”

(Photo used under the Fair Use Doctrine.)

Courage at Twilight: A Kind Doctor

“Tell me what’s happening,” Dr. Hawkins asked me over the phone. I was not sure how to express the subtle changes my siblings and I had observed, but I breathed deeply and tried. Well, first, there’s her memory. She forgets what I told her just minutes or hours before. And she’s forgetting the names of familiar people and places. (Heck, I do that, too.) Second, she becomes easily confused. I explain simple things several times before she comprehends, and I interpret for her much of her mail. Third, anxiety. When something needs doing, it needs doing right now. Small things distress her, until I reassure her everything will be fine. And when go for a drive, she points to cows and clouds and airplanes and exclaims, “Look, a cow!…a cloud!…an airplane!” “Well, I think you’ve expressed it pretty well,” the doctor confirmed. “Bring her to my office, and we’ll talk.” Raising with Mom the subject of a doctor visit to discuss memory and confusion hurt her feelings, though I had tried to gentle and assuring. “I don’t remember forgetting anything,” she worried. Hawkins was so kind, entering the examination room with “Hello Lucille!” and pulling her into an embrace. He thanked her for having the courage and wisdom to have this hard conversation, but assured her she had done the right thing. “If we catch dementia early, we have ways of slowing it down. (And don’t worry about the name: dementia is just the medical term for memory loss.) If you had waited until there was a real problem, there is little we could have done. Dementia is caused by brain atrophy and is not reversable. You were right to come in early.” An MRI two years prior (which Mom remembered but the doctor and I had forgotten) had revealed mild brain atrophy, normal for her age, so the doctor moved right into Mom’s treatment plan, which included taking a new once-a-day pill and doing lots of word puzzles and needlepoints. “Thank you so much for coming in to talk with me about this difficult subject,” he said. “You’re doing great.” Mom left the doctor’s office feeling good about herself and her future, and I left feeling grateful for a kind doctor.